Researchers from PUCRS' School of Medicine and BraIns involved in groundbreaking investigation

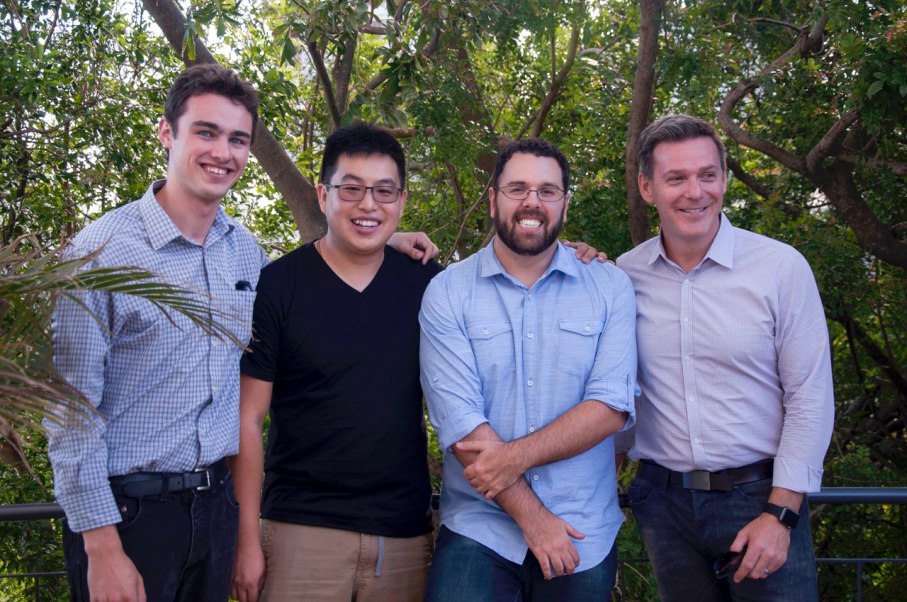

From left to right: researchers Paul Marshall, Xiang Li, Rodrigo Grassi-Oliveira, Timothy Bredy / Image: Personal Archive

Have you ever thought that chemical changes to DNA could lead to the extinction of fear memories? A study developed by the Brain Institute of the University of Queensland, Australia, in collaboration with researchers from the School of Medicine of PUCRS and Brain Institute of RS (BraIns), has shown that it may now be possible. The findings were published in the world’s most important neuroscience journal, Nature Neuroscience, in February.

The study has found chemical changes to the DNA that enhances the ability to extinguish fear. The innovative findings could help guide the development of treatments to be used in the future, such as gene therapies. This type of therapy could be used to make the fear-processing genes dormant and consequently help people who suffer from certain phobias or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Former PUCRS faculty served as leading researcher

This investigation was headed by Xiang Li, a student advised by Dr Timothy Bredy, who is responsible for the article published in Nature Neuroscience. Bredy came to PUCRS as a visiting professor from 2014, 2015 and 2016. In his view, although fear is an important survival mechanism, so would be the ability to silence it when it is not necessary. “Fear extinction works as a counter-balance to fear. It involves the creation of new non-fearful memories with similar environmental elements that compete with the original fear memory”, says Bredy on the website of the University of Queensland.

Research has shown that a small region of the pre-frontal cortex (PFC) plays a critical role in the learning processes and fear-extinction memories. It has also shown that the activity of neurons in this region is under strict epigenetic control. “DNA is not static. Chemical tags on DNA bases act like a dimmer switch that can turn up or turn down the expression of a gene”, he said.

Experimental research

The researchers made the discovery by placing mice in a box where they heard a particular tone, which was immediately followed by a mild foot-shock. The mice quickly associated the sound with the foot-shock and “froze” when they heard it. To encourage fear extinction, the mice were then placed in a different box, where they repeatedly heard the same sound, but did not receive any foot-shocks When the mice were returned to the original box, they were no longer afraid of the sound for the memory had been extinguished.

Researchers looked at the DNA of the neurons in the pre-frontal cortex in these animals and found the presence of a chemical change to the adenine, N6-methyl-2-deoxyadenosine (m6dA), in more than 2,800 locations across the genome. For a long time, it was thought that cytosine (C) was the only DNA base that could be modified through methylation. However, now it is clear that adenosine (A) can also be chemically marked.

The team also concluded that fear extinction memories form thanks to an adenine modification that increases the activity of certain genes. In other words, this epigenetic change to the DNA of these neurons will only occur during fear extinction.

“Understanding the fundamental mechanism of how gene regulation associated with fear extinction could provide future targets for therapeutic intervention in fear-related anxiety disorders”, Bredy says

PUCRS participation in the study

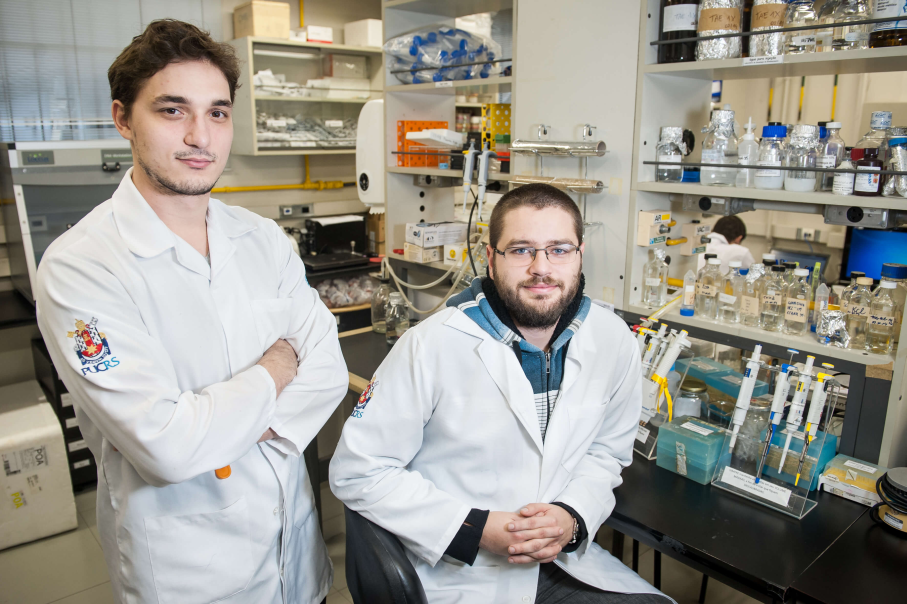

Wearick and Viola, post-doctoral researchers at the School of Medicine of PUCRS and BraIns RS / Image: Bruno Todeschini

PUCRS, through its School of Medicine‘s interdisciplinary research group Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience (DCNL) made a contribution to the study. Headed by psychiatrist Dr Rodrigo Grassi-Oliveira, who also serves as a researcher at the Brain Institute of RS, the group collaborates with researchers from different areas from all across the globe.

Grassi-Oliveira has completed his post-doctoral research in Australia and made the beginning of the collaborative activities between the two institutions a reality. He brought Dr Bredy to PUCRS three times and sent two students to Bredy’s laboratory, while he was working at the University of California, Irvine. “I began a collaborative project with a laboratory in Australia to exchange practices in the area of neuroepigenetics and to make the mobility of students and faculty possible”, Grassi-Oliveira says.

Dr Thiago Viola and Dr Luis Eduardo Wearick, who are currently serving as post-doctoral researchers at PUCRS’ School of Medicine and BraIns have played an active role in this investigation. They completed an entire year of experiments as they were working on their doctoral internships under the CNPq – Ciências Sem Fronteiras’ program Special Visiting Professor.

“One of the goals of these collaborative activities was to offer a training program into epigenetics and take part in the ongoing projects. It is very rewarding to have worked with people from several universities and laboratories from all over the world in such an important project as this”, Wearick said. Viola is proud to have the chance to use the knowledge he has gained. “I’m very happy to have made a contribution to this research and gained very specific knowledge on epigenetics to be replicated at our research group at PUCRS”.