Brazil-Australia Cultural Adaptive Practices

Brazil-Australia Cultural Adaptive Practices

Brazil and Australia both have tens of thousands of years of human interaction with their unique and varied environments. The dynamics of these indigenous groups and the plurality of voices from their contemporary descendents are essential in exploring the complex relationship between natural ecosystems, human adaptation and modification of the environment, history, and cosmology (or how we ‘view’ and take care of our place in the world). By comparing two large, unique and diverse narratives of indigenous interaction with the environment, in Brazil and Australia, we can illustrate the complexity of human adaptation and learn applicable lessons about our relationship with the environment and society today.

Archaeology, anthropology, and history are essential elements to understand and explain how these dynamics have played out in specific parts of the world. The following ‘adaptive’ modules compare case studies from the indigenous societies from both countries – by comparing specifics we can see more clearly how differing environmental circumstances influence cultural choices, and how, in turn, cultural developments influence future adaptive behaviors. It is a fascinating process that has a long history, but is still very much unfolding on the planet today

CASE STUDIES: Cultural Adaptations and Comparisons

Language:

Proposal

Proposal

Although we often think of language as an efficient means of conveying practical and emotional messages and ideas between members of the community, it is so much more. The language we use shapes and organizes the way we think about and inhabit our worlds. Each language reflects a culture’s ‘worldview’ or cosmology and expresses truths about the fundamental values and concerns of a culture. At the same time, the vocabulary and syntax of each language can inform the development and decisions of the practitioner, on individual and group levels. In this sense, when we approach the indigenous languages of Australia, Brazil or any other part of the globe and can tally hundreds of unique languages and thousands of dialects, we are not simply confronting an array of systems of grammatical rules and words, but varieties of explaining, naming, dividing, uniting, and ‘being in’ the world. For this reason, languages are often key for gaining any real access into the inner workings of each culture and beginning to appreciate how very different each culture is at the core.

Sources:

Povos Indígenas do Brasil. Povos Indígenas no Brasil – https://pib.socioambiental.org/

Proposal

Although we often think of language as an efficient means of conveying practical and emotional messages and ideas between members of the community, it is so much more. The language we use shapes and organizes the way we think about and inhabit our worlds. Each language reflects a culture’s ‘worldview’ or cosmology and expresses truths about the fundamental values and concerns of a culture. At the same time, the vocabulary and syntax of each language can inform the development and decisions of the practitioner, on individual and group levels. In this sense, when we approach the indigenous languages of Australia, Brazil or any other part of the globe and can tally hundreds of unique languages and thousands of dialects, we are not simply confronting an array of systems of grammatical rules and words, but varieties of explaining, naming, dividing, uniting, and ‘being in’ the world. For this reason, languages are often key for gaining any real access into the inner workings of each culture and beginning to appreciate how very different each culture is at the core.

Sources:

Povos Indígenas do Brasil. Povos Indígenas no Brasil – https://pib.socioambiental.org/

Linguistic diversity on the brink

Linguistic diversity on the brink

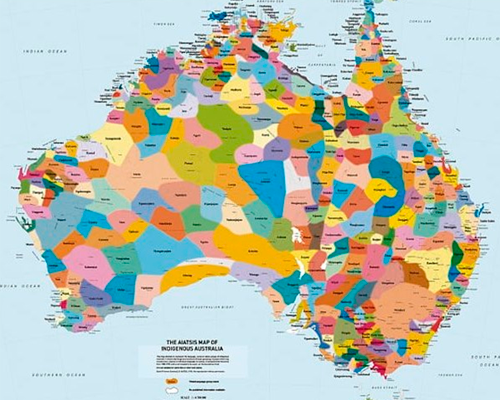

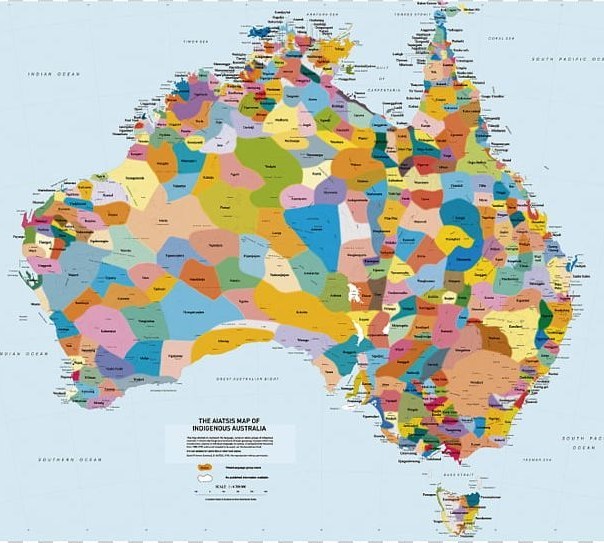

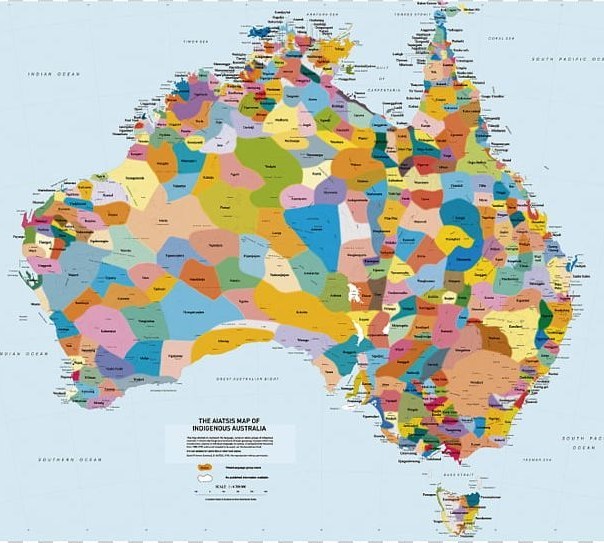

Since the arrival of European colonists there have been systematic measures intended to eradicate indigenous language diversity and institutionalize English as the language of the continent. In many instances, generations of indigenous speakers have had to keep their native tongue secret, but amazingly, as many as 300 of these languages survive today. Some are only spoken by a few hundred people, while others number in the thousands. In all cases, the language is foundational to the collective identity of the people and often the only way of conveying the ideas and values that are unique to each culturally adaptive model. If the language goes extinct, many concepts disappear with it.

Sources:

The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies: https://aiatsis.gov.au/

Living Languages: https://shop.aiatsis.gov.au/pages/map-licensing

Linguistic diversity on the brink

Since the arrival of European colonists there have been systematic measures intended to eradicate indigenous language diversity and institutionalize English as the language of the continent. In many instances, generations of indigenous speakers have had to keep their native tongue secret, but amazingly, as many as 300 of these languages survive today. Some are only spoken by a few hundred people, while others number in the thousands. In all cases, the language is foundational to the collective identity of the people and often the only way of conveying the ideas and values that are unique to each culturally adaptive model. If the language goes extinct, many concepts disappear with it.

Sources:

The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies: https://aiatsis.gov.au/

Living Languages: https://shop.aiatsis.gov.au/pages/map-licensing

Language as a Guide to History

Language as a Guide to History

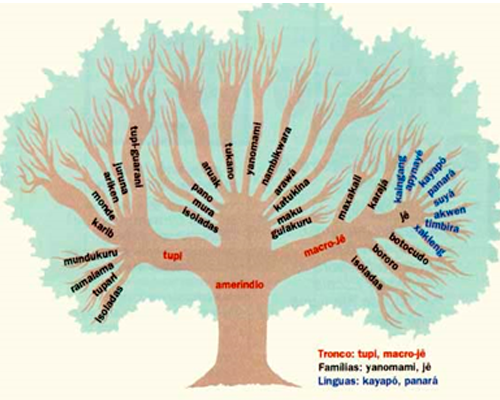

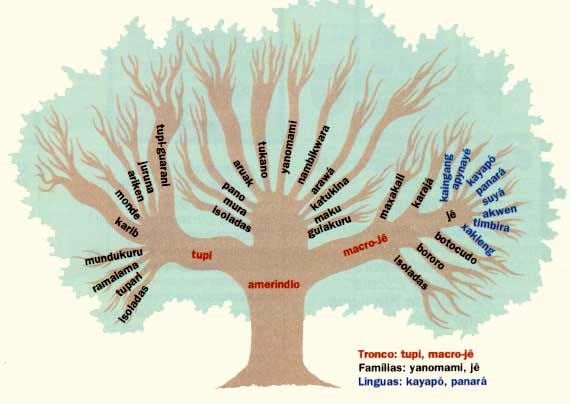

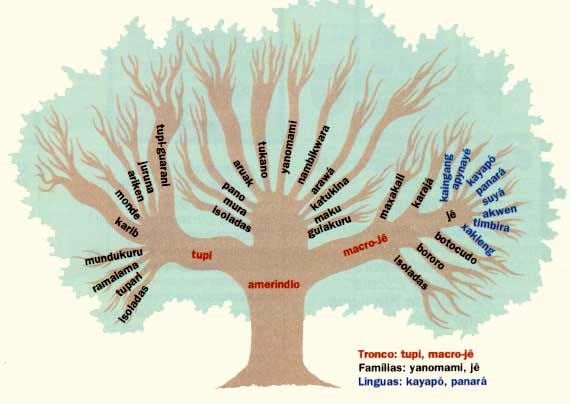

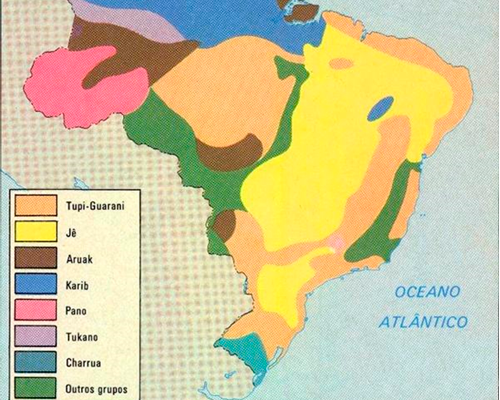

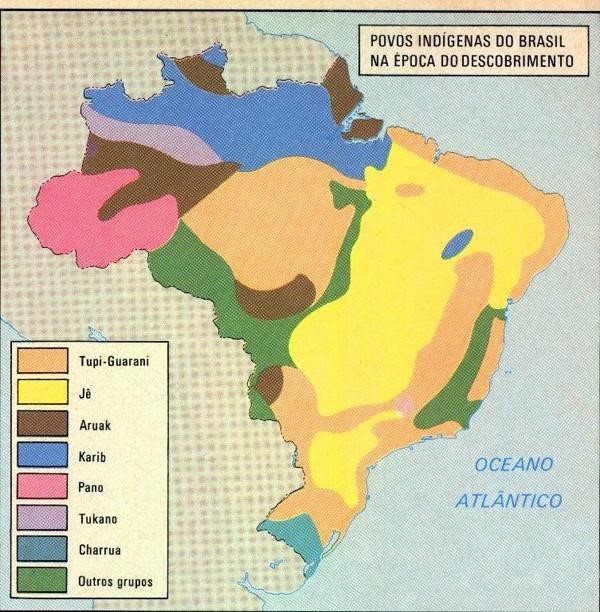

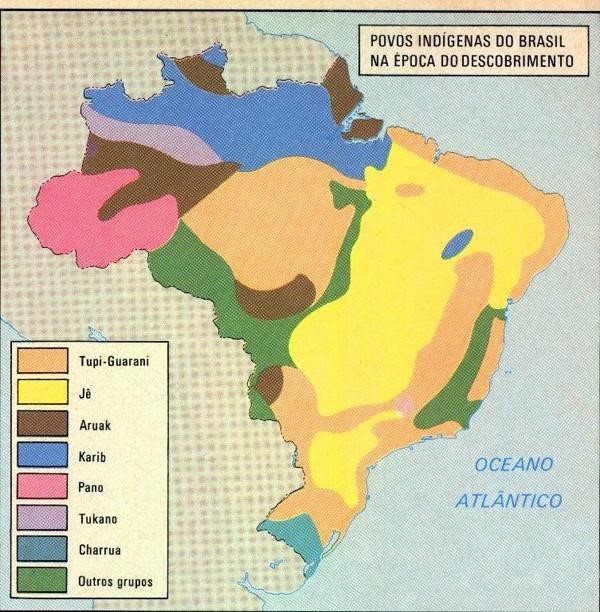

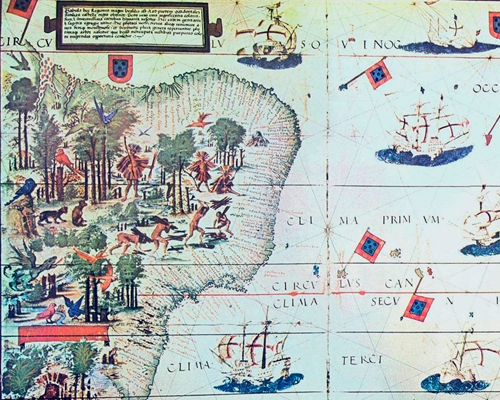

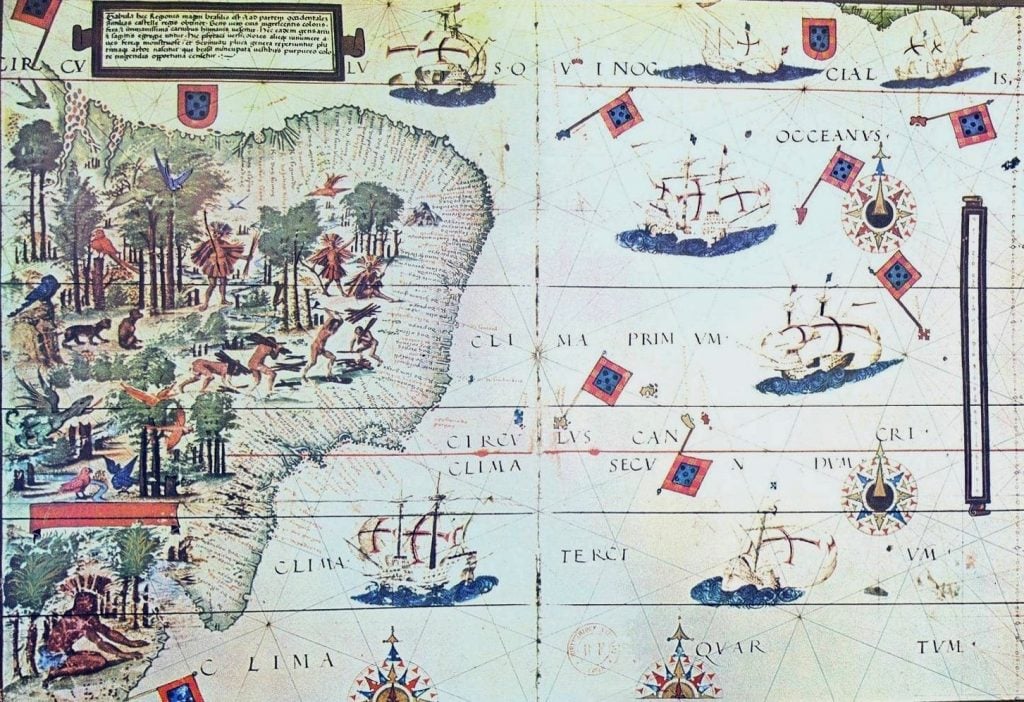

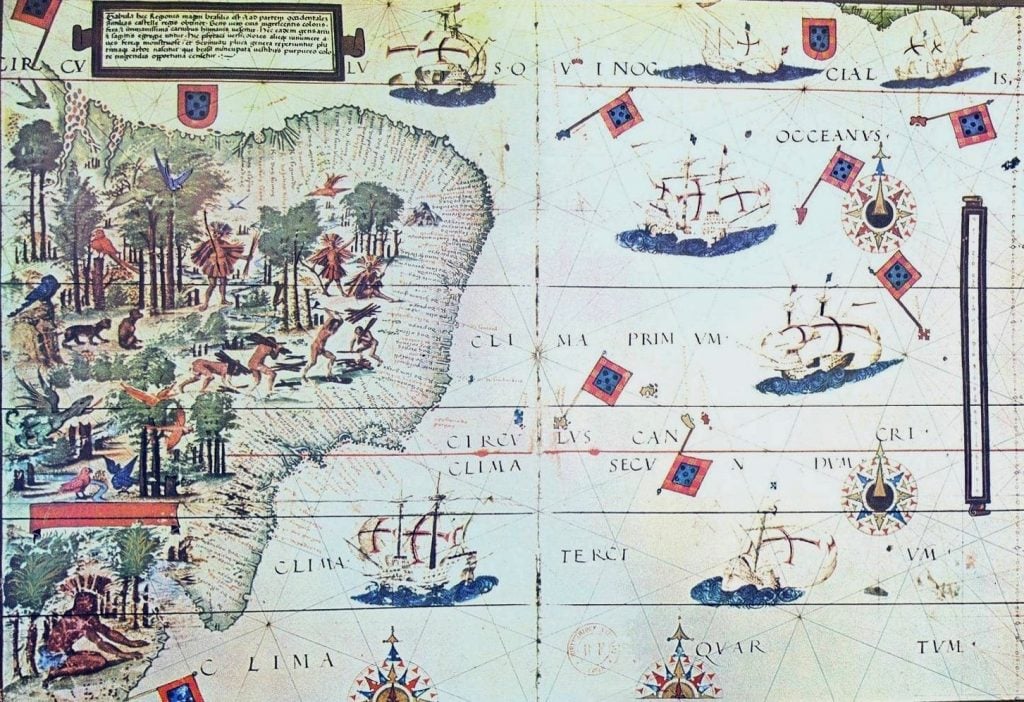

It is estimated that there were at least 1000 distinct languages in Brazil at the time of the Portuguese arrival – today there are only 160 remaining in use. Just like comparing the DNA of species to rebuild the story of biological evolution, languages can be compared to piece together the stories of their common roots and divergences. Especially in hot, humid places like Brazil, archaeological remains can be very hard to recover due to their rapid deterioration. In these situations, the living languages of today’s indigenous communities can be incredible resources for working backwards to understand the geographical and historical movements of various societies over long periods of time. As the languages continue to disappear or fall out of use, the invaluable historical knowledge they contain, which is only just beginning to be studied, also ceases to exist.

Povos índigenas ao descobrimento.

http://noamazonaseassim.com.br/as-tribos-indigenas-do-estado-do-amazonas.

Language as a Guide to History

It is estimated that there were at least 1000 distinct languages in Brazil at the time of the Portuguese arrival – today there are only 160 remaining in use. Just like comparing the DNA of species to rebuild the story of biological evolution, languages can be compared to piece together the stories of their common roots and divergences. Especially in hot, humid places like Brazil, archaeological remains can be very hard to recover due to their rapid deterioration. In these situations, the living languages of today’s indigenous communities can be incredible resources for working backwards to understand the geographical and historical movements of various societies over long periods of time. As the languages continue to disappear or fall out of use, the invaluable historical knowledge they contain, which is only just beginning to be studied, also ceases to exist.

Povos índigenas ao descobrimento.

http://noamazonaseassim.com.br/as-tribos-indigenas-do-estado-do-amazonas.

Human-Animal Relationships:

Presentation

Presentation

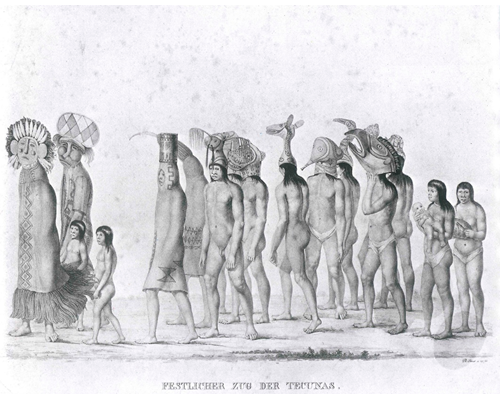

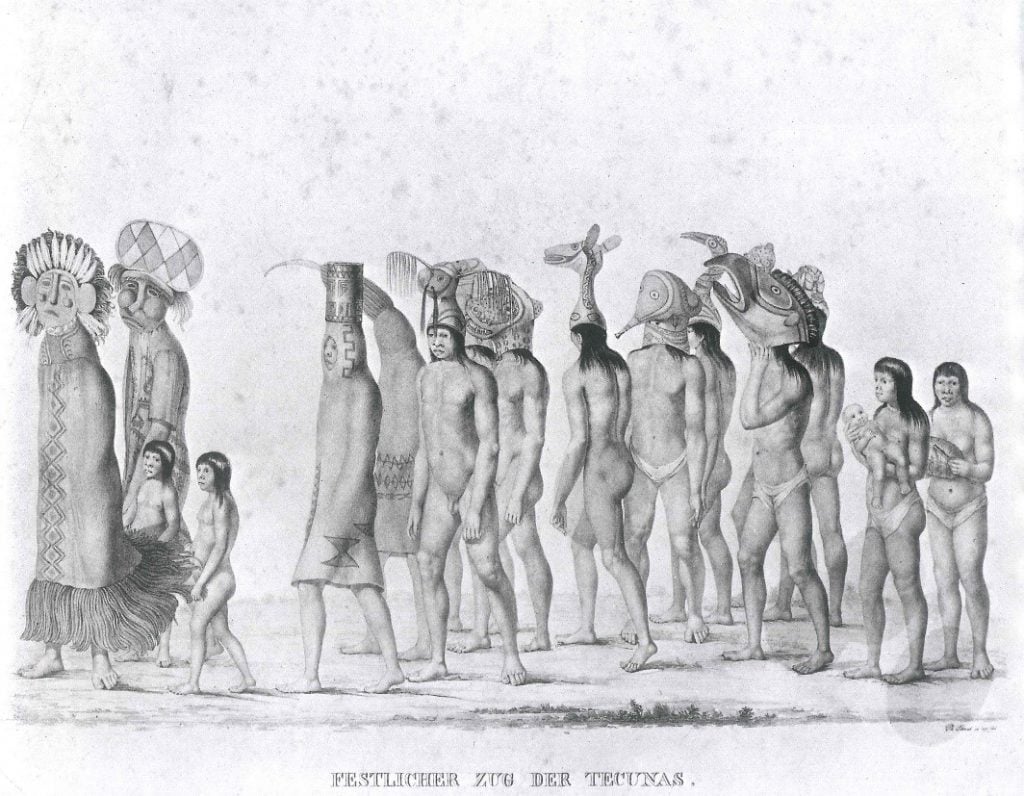

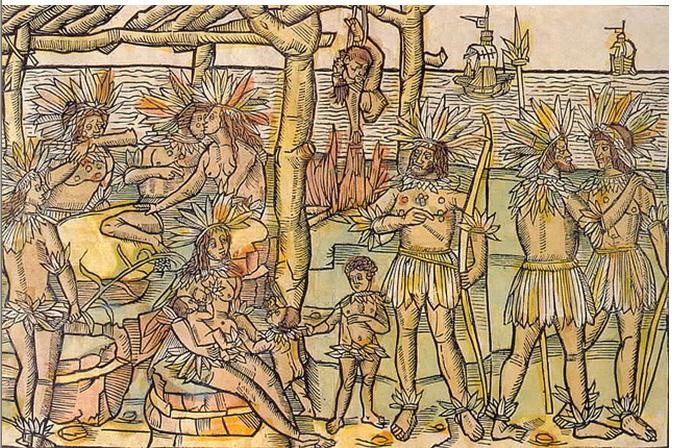

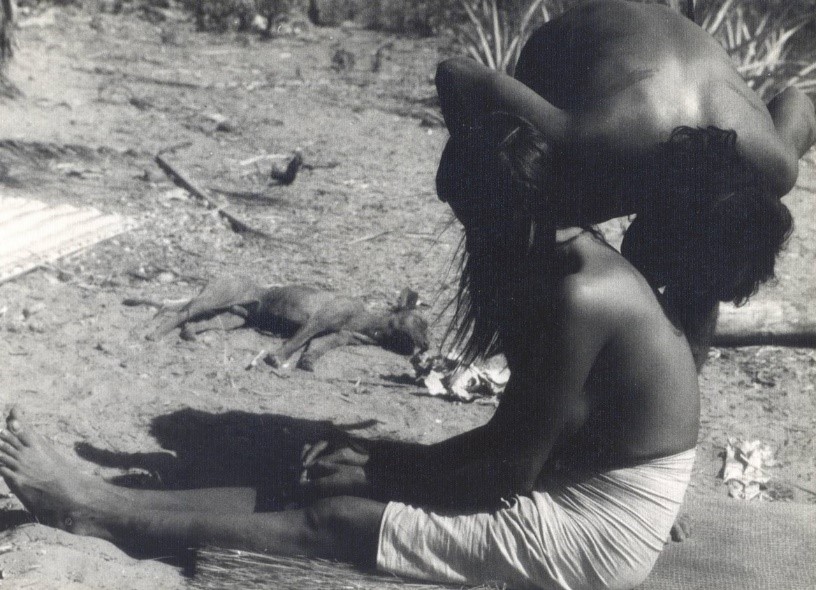

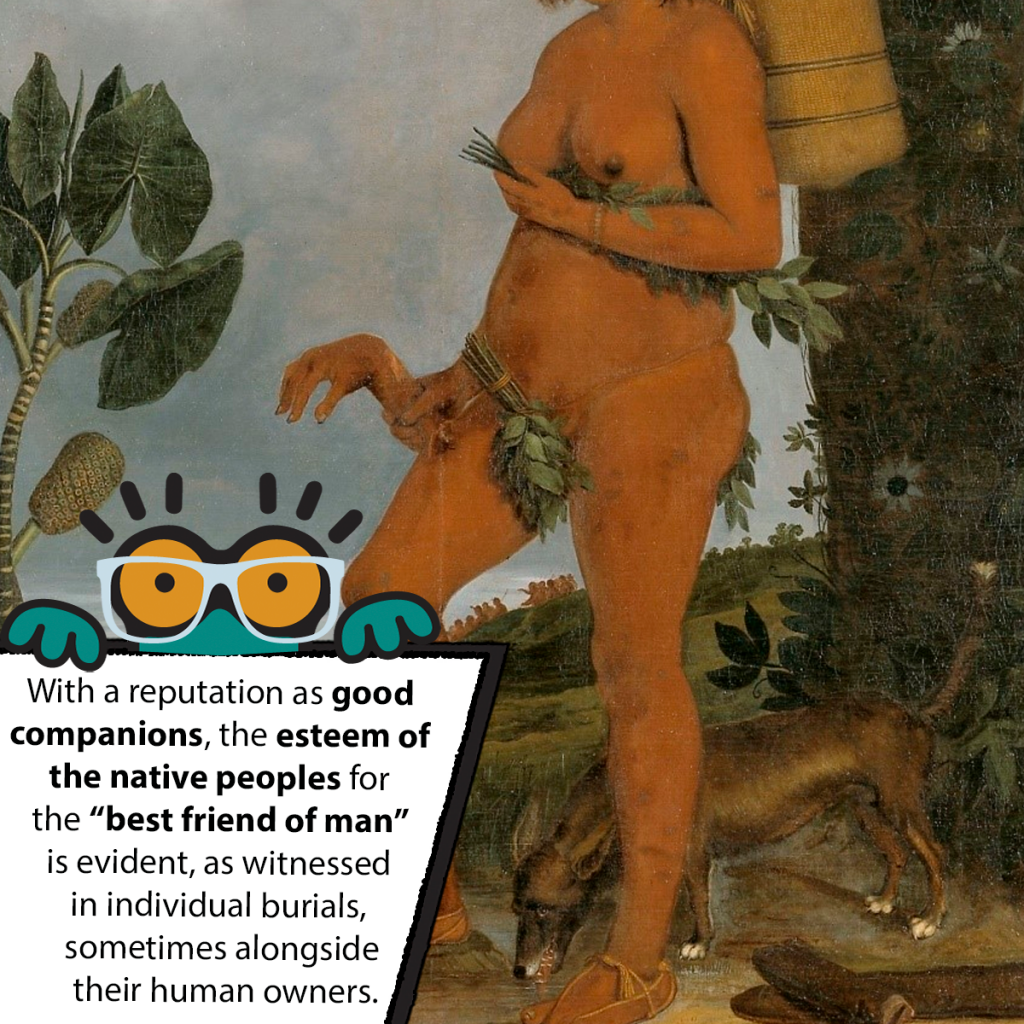

The cosmological and practical attitudes different societies have towards other living beings can be quite startlingly different and shape many aspects of day-to-day life. While industrialized societies tend to approach the natural world as a source of raw materials for human utility and consumption, but by exploring indigenous worldviews on the subject, we find a dizzying variety regarding the ideal arrangement between humanity and fellow beings. Though they are by no means uniform in detail or outcome, these indigenous ‘ecological cosmologies’ tend to offer a highly complex and nuanced arrangement between the species that seems lacking in profit-oriented industrialized societies.

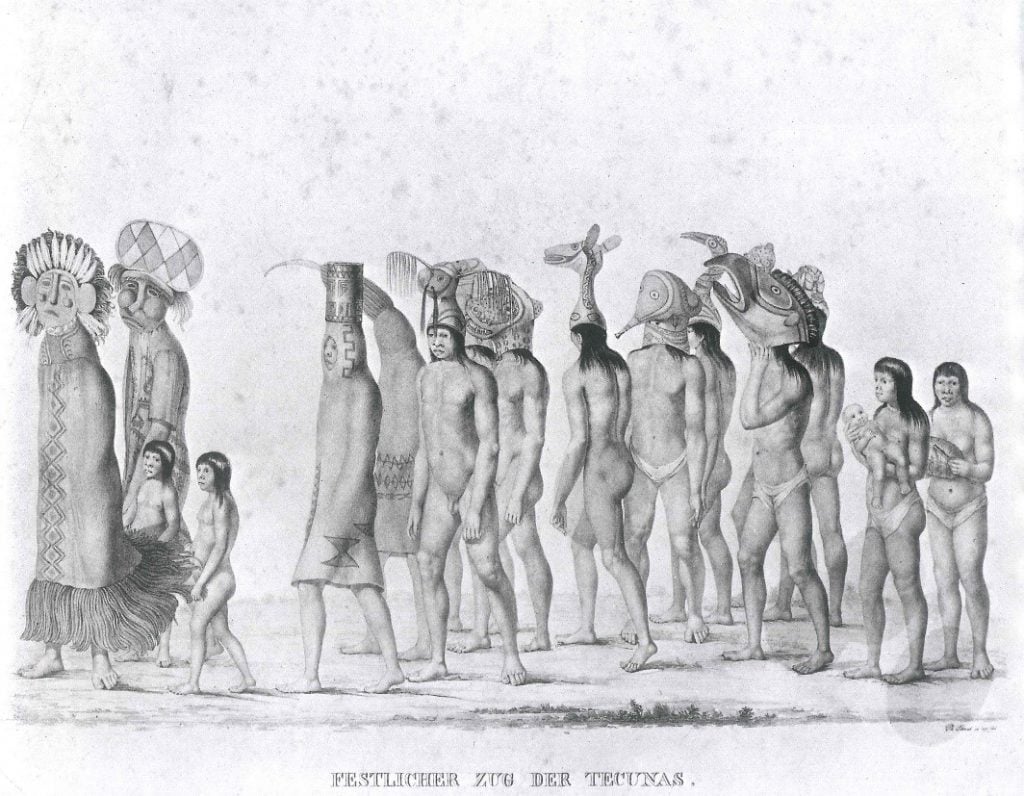

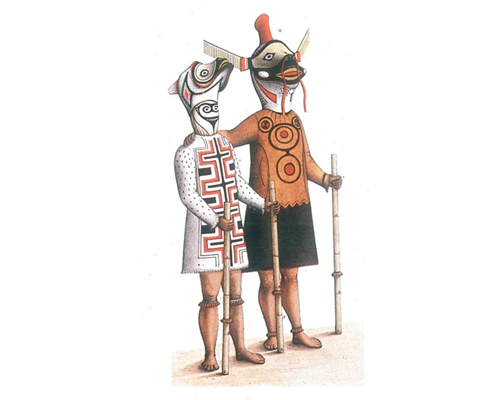

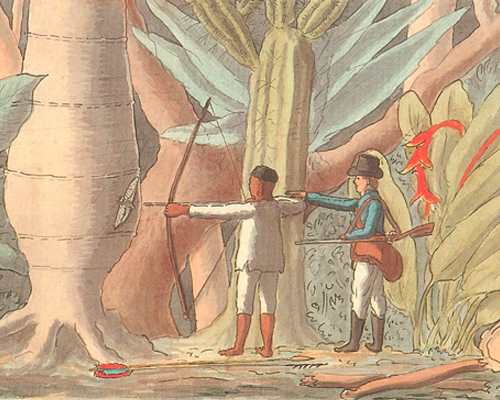

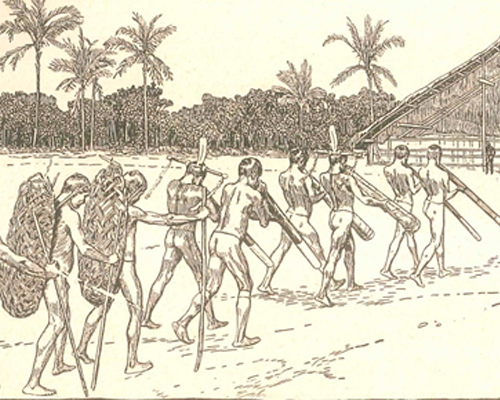

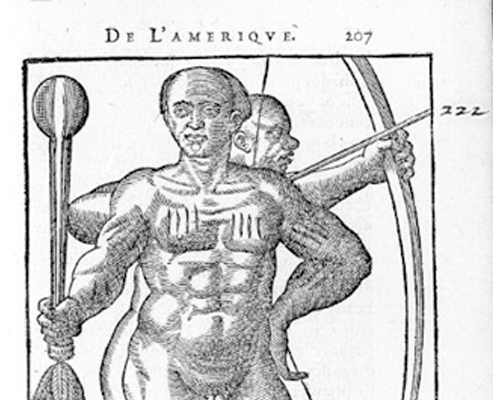

Tecuna people during a ceremony, dressed in animal-human ‘clothes’. (Spix and Martius, 1823-31).

Sources:

SPIX, J. B. von; MARTIUS, C.F.P. von. Reise in Brasilien in den Jahren 1817 bis 1820. München, 1823-31.

Presentation

The cosmological and practical attitudes different societies have towards other living beings can be quite startlingly different and shape many aspects of day-to-day life. While industrialized societies tend to approach the natural world as a source of raw materials for human utility and consumption, but by exploring indigenous worldviews on the subject, we find a dizzying variety regarding the ideal arrangement between humanity and fellow beings. Though they are by no means uniform in detail or outcome, these indigenous ‘ecological cosmologies’ tend to offer a highly complex and nuanced arrangement between the species that seems lacking in profit-oriented industrialized societies.

Tecuna people during a ceremony, dressed in animal-human ‘clothes’. (Spix and Martius, 1823-31).

Sources:

SPIX, J. B. von; MARTIUS, C.F.P. von. Reise in Brasilien in den Jahren 1817 bis 1820. München, 1823-31.

The ‘warpiri’ of the Yarralin social ecology

The ‘warpiri’ of the Yarralin social ecology

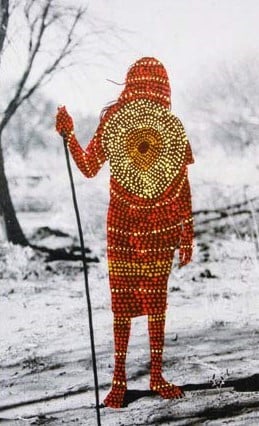

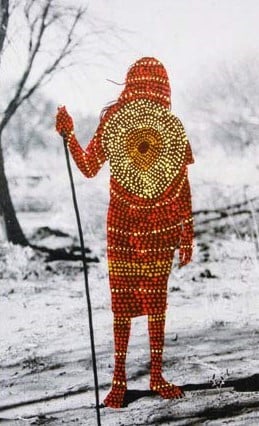

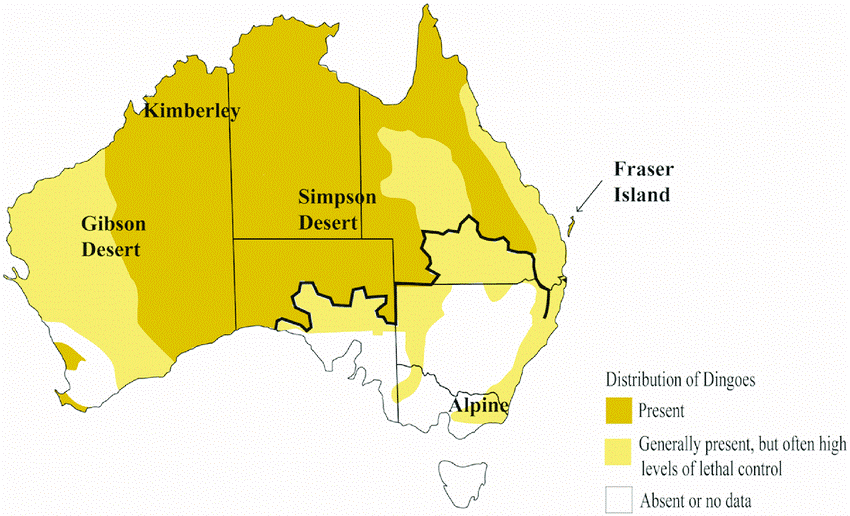

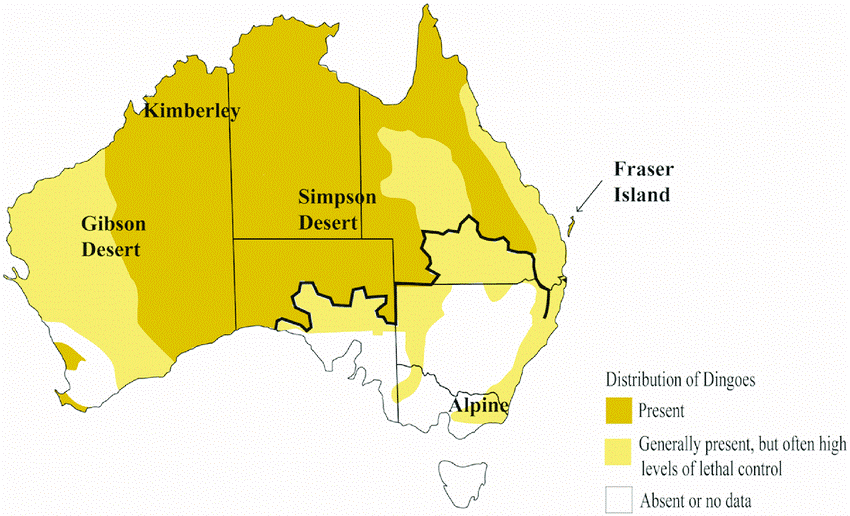

The Yarralin First Nations community, which includes several language groups, is located in the Northern Territory. This group of about 300 permanent residents present an incredibly complex lineage scheme that determines relationships between members of the community based on matrilineal structure, kinship, and responsibilities, but also defines each person’s relationship to a particular season, elements, and their essential animal or warpiri.

Depending on your specific cosmological kinship, which is determined through a series of measures, you may or may not have the same warpiri with your ‘blood’ relatives (a concept that doesn’t quite work with the Yarralin kinship model). Whatever the case, your relationship with your warpiri animal is concrete and lifelong. Eating this particular animal would amount to a form of cosmological cannibalism and some even claim they smell human flesh when their own warpiri is cooked.

When there is a death in the community, a certain amount of time is allowed for grief where the animal species associated with that diseased member is not in any way harmed or hunted. In this small snapshot of a much larger and more complicated cosmo-ecology, we can see the lines between kinship-family and animal life forms are interrelated at a level of intimacy and sophistication that only hints at the depth of this model.

Sources:

WATERHOUSE, P. Restricted Images: Made with the Warlpiri of Central Australia. Spbh Editions. 2018.

The ‘warpiri’ of the Yarralin social ecology

The Yarralin First Nations community, which includes several language groups, is located in the Northern Territory. This group of about 300 permanent residents present an incredibly complex lineage scheme that determines relationships between members of the community based on matrilineal structure, kinship, and responsibilities, but also defines each person’s relationship to a particular season, elements, and their essential animal or warpiri.

Depending on your specific cosmological kinship, which is determined through a series of measures, you may or may not have the same warpiri with your ‘blood’ relatives (a concept that doesn’t quite work with the Yarralin kinship model). Whatever the case, your relationship with your warpiri animal is concrete and lifelong. Eating this particular animal would amount to a form of cosmological cannibalism and some even claim they smell human flesh when their own warpiri is cooked.

When there is a death in the community, a certain amount of time is allowed for grief where the animal species associated with that diseased member is not in any way harmed or hunted. In this small snapshot of a much larger and more complicated cosmo-ecology, we can see the lines between kinship-family and animal life forms are interrelated at a level of intimacy and sophistication that only hints at the depth of this model.

Sources:

WATERHOUSE, P. Restricted Images: Made with the Warlpiri of Central Australia. Spbh Editions. 2018.

‘Multinaturalism’ of Amazonian relations

‘Multinaturalism’ of Amazonian relations

In some indigenous societies, that variety of natural beings, including humans, does not represent a hierarchy at all, but different physical manifestations of social beings. Amazonian ‘perspectivism’ sees animals as humans, animals; spirits, plants, and even objects as each have their own legitimate social and spiritual operations. In the same way the human society tends to view itself as the subject around which the rest of the beings operate, the Amerindian cosmology allows for the other beings and objects a similar position as ‘people’ in their worldview.

They have their own homes or villages, eat delicious meals, converse, and perform rituals. In this system it becomes clearer why shamans dress themselves in animal skins when entering in the spiritual space of said animal – they are prepared to participate in that specific ‘jaguar’ society (for example) only in the technological apparatus of the jaguar clothing. This multinatural view of the universe allows for a mutual respect and interaction with non-human beings that is generally closed off to those in industrialized societies that define ‘Culture’ as opposed to ‘Nature’.

Sources:

FERREIRA, A. R. Viagem filosófica ao Rio Negro. Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi 1983 [1787]).

VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, E. Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivism. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 4(3): 469-488, 1998.

‘Multinaturalism’ of Amazonian relations

In some indigenous societies, that variety of natural beings, including humans, does not represent a hierarchy at all, but different physical manifestations of social beings. Amazonian ‘perspectivism’ sees animals as humans, animals; spirits, plants, and even objects as each have their own legitimate social and spiritual operations. In the same way the human society tends to view itself as the subject around which the rest of the beings operate, the Amerindian cosmology allows for the other beings and objects a similar position as ‘people’ in their worldview.

They have their own homes or villages, eat delicious meals, converse, and perform rituals. In this system it becomes clearer why shamans dress themselves in animal skins when entering in the spiritual space of said animal – they are prepared to participate in that specific ‘jaguar’ society (for example) only in the technological apparatus of the jaguar clothing. This multinatural view of the universe allows for a mutual respect and interaction with non-human beings that is generally closed off to those in industrialized societies that define ‘Culture’ as opposed to ‘Nature’.

Sources:

FERREIRA, A. R. Viagem filosófica ao Rio Negro. Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi 1983 [1787]).

VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, E. Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivism. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 4(3): 469-488, 1998.

Architecture

Appearance

Appearance

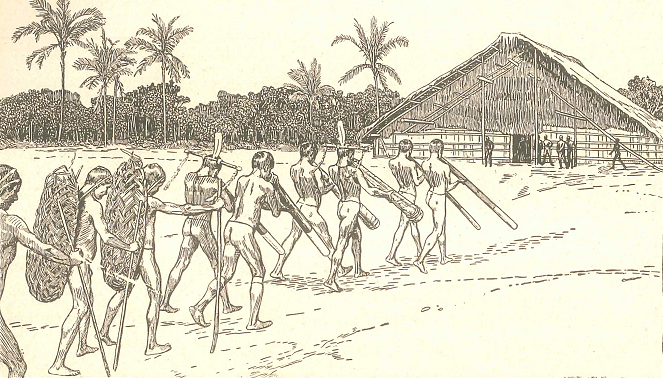

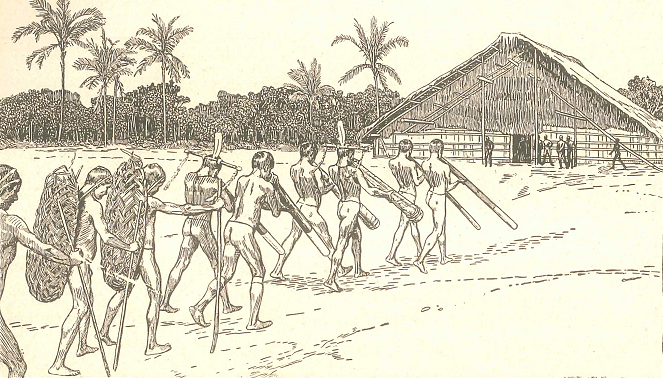

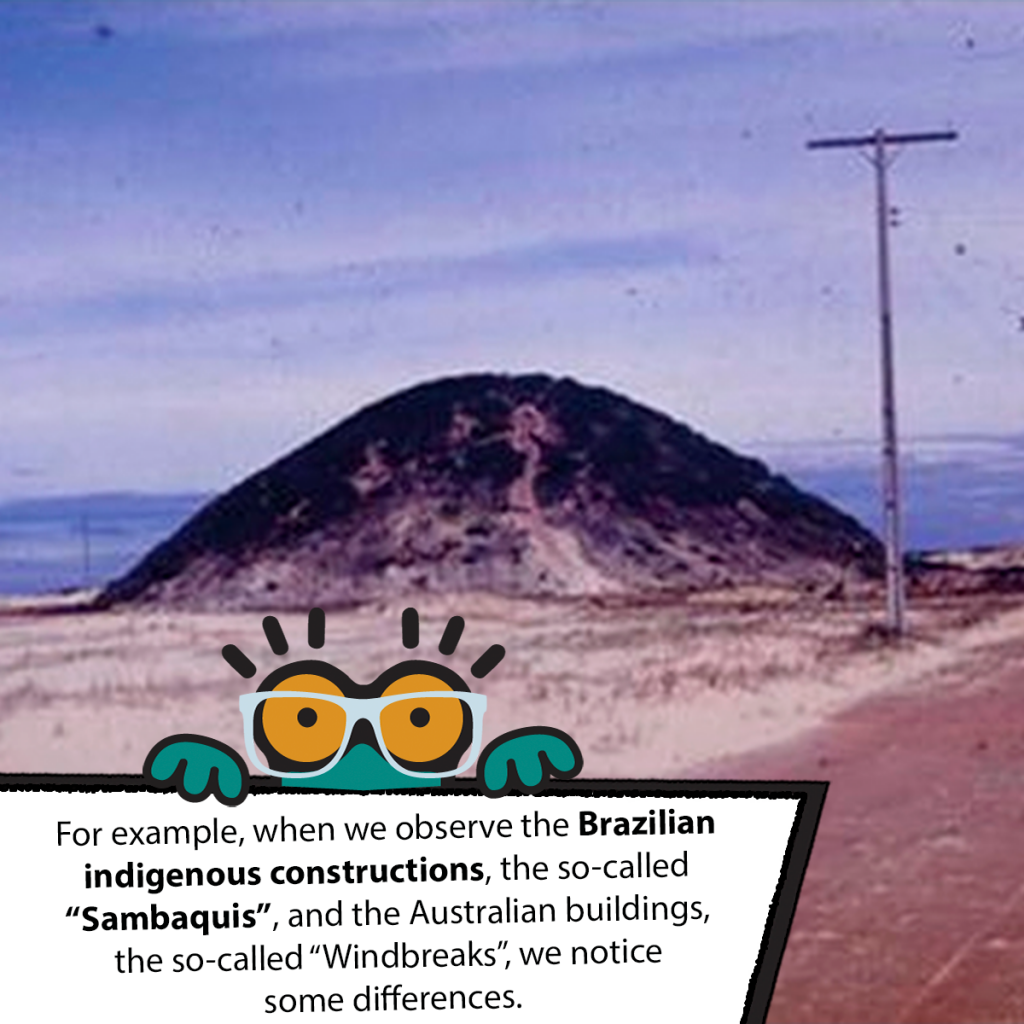

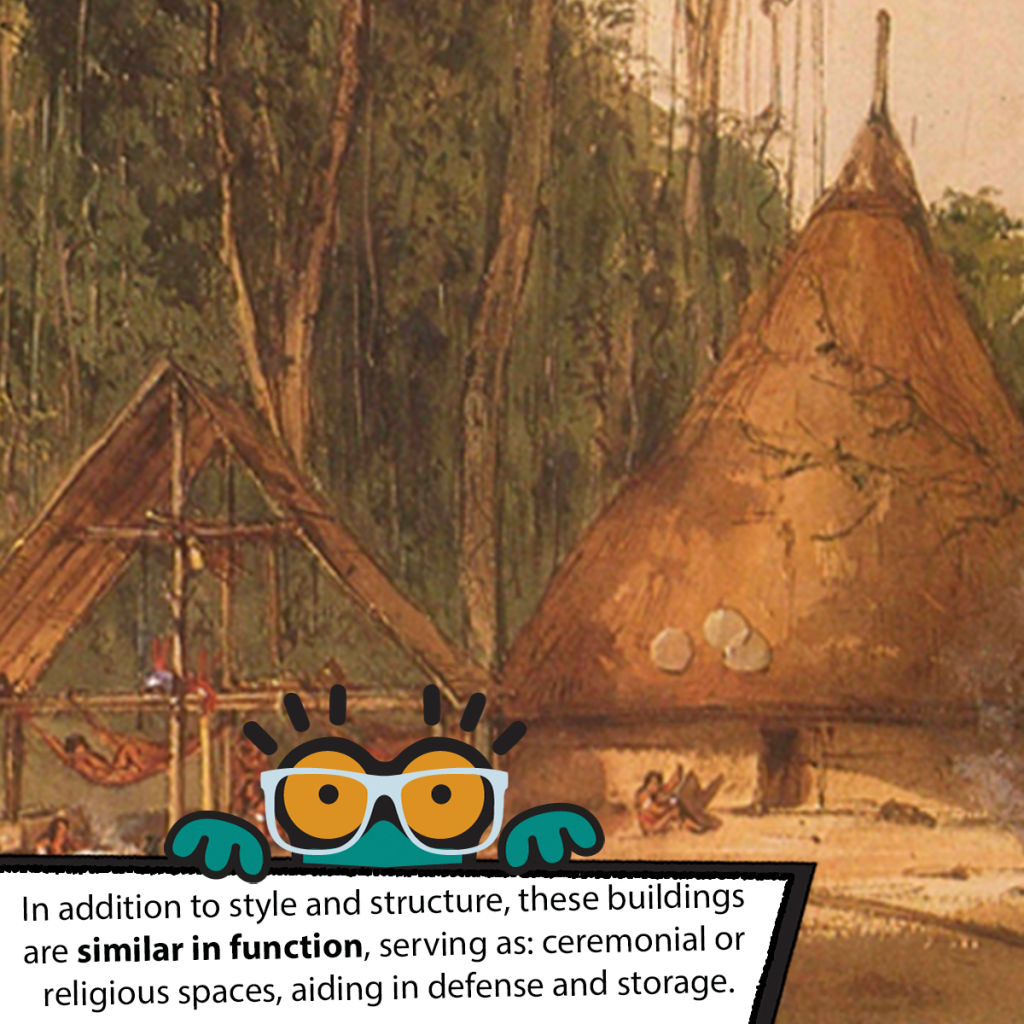

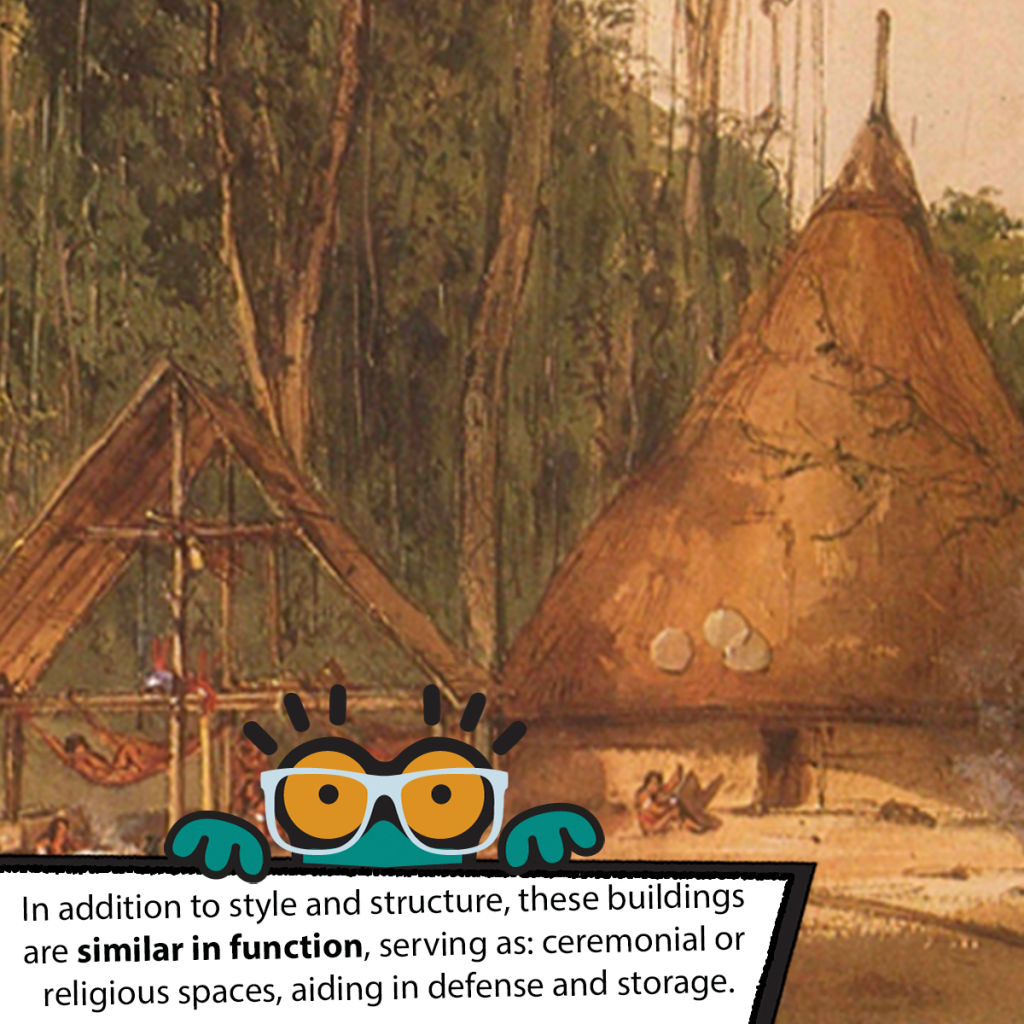

Human societies often build upon their natural surroundings in the form of permanent or temporary structures we call architecture. These can function as living spaces (our concept of ‘home’-oikos), ceremonial or religious spaces, assist in defense, storage, or serve a multi-functional purpose. For understanding architecture, it helps to approach it as both an object and an environment.

Indigenous architecture worldwide is unique in both form and function depending on where one looks. Like all adaptive technologies, very often the materials and construction of the ‘buildings’ are reflective of the resources and condition the specific natural environment offers, and Brazil and Australia’s architectural legacy fits this mold perfectly.

SCHOMBURGK, R. Reports to the Royal Geographical Society. Question de la frontière entre la Guyane Britannique et Brésil. London: Harrison &Sons.1903 [1836-39]

Appearance

Human societies often build upon their natural surroundings in the form of permanent or temporary structures we call architecture. These can function as living spaces (our concept of ‘home’-oikos), ceremonial or religious spaces, assist in defense, storage, or serve a multi-functional purpose. For understanding architecture, it helps to approach it as both an object and an environment.

Indigenous architecture worldwide is unique in both form and function depending on where one looks. Like all adaptive technologies, very often the materials and construction of the ‘buildings’ are reflective of the resources and condition the specific natural environment offers, and Brazil and Australia’s architectural legacy fits this mold perfectly.

SCHOMBURGK, R. Reports to the Royal Geographical Society. Question de la frontière entre la Guyane Britannique et Brésil. London: Harrison &Sons.1903 [1836-39]

Brazil’s mound constructions

Brazil’s mound constructions

Tens of thousands of mound constructions, built by a variety of societies over thousands of years, dot the country of Brazil. Often in clusters or meticulously arranged groups, the one feature they have in common is their method of construction of earth or shell built upwards to an elevated, flattened platform. They range in size from enormous to small; in some instances, they appeared to have wooden constructions on top, but in other cases not. Sometimes they have human burials, valuable items like ceramics, weapons or animal remains inserted inside their very walls. Some, especially near the beach, may be constructed from the litter of marine animal bodies, while others appear to have required hundreds of people working a long time to deliberately build. In essence, they are too varied to define singularly.

In some ways, it is like the ‘framing’ style of construction used by modern western builders – it can be applied equally for a small house, a church, a hospital, or a theater. Likewise, mound buildings appear to be a technique of architecture rather than defining any particular use. In some instances, the arrangement of the mounds towards specific points in the horizon and their associated artifacts, indicate a ritualistic or cosmological use. While others have studied mounds that are at places designed for the widest possible view of waterways, or high on plateaus, that seem to point to a defensive or political controlling functionality.

Sources:

ALT, S. M. Histories of Mound Building and Scales of Explanation in Archaeology. In: BERNBECK, R.; MCGUIRE, R. H. (Org.) Ideologies In Archaeology. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2011. cap. 8, p. 194-211.

BONOMO, M.; POLITIS, G. G. Mound Building, Social Complexity and Horticulture in the Lower Paraná. In: SMITH, C. (Org.) Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. New York: Springer, 2018. p. 1-22.

Brazil’s mound constructions

Tens of thousands of mound constructions, built by a variety of societies over thousands of years, dot the country of Brazil. Often in clusters or meticulously arranged groups, the one feature they have in common is their method of construction of earth or shell built upwards to an elevated, flattened platform. They range in size from enormous to small; in some instances, they appeared to have wooden constructions on top, but in other cases not. Sometimes they have human burials, valuable items like ceramics, weapons or animal remains inserted inside their very walls. Some, especially near the beach, may be constructed from the litter of marine animal bodies, while others appear to have required hundreds of people working a long time to deliberately build. In essence, they are too varied to define singularly.

In some ways, it is like the ‘framing’ style of construction used by modern western builders – it can be applied equally for a small house, a church, a hospital, or a theater. Likewise, mound buildings appear to be a technique of architecture rather than defining any particular use. In some instances, the arrangement of the mounds towards specific points in the horizon and their associated artifacts, indicate a ritualistic or cosmological use. While others have studied mounds that are at places designed for the widest possible view of waterways, or high on plateaus, that seem to point to a defensive or political controlling functionality.

Sources:

ALT, S. M. Histories of Mound Building and Scales of Explanation in Archaeology. In: BERNBECK, R.; MCGUIRE, R. H. (Org.) Ideologies In Archaeology. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2011. cap. 8, p. 194-211.

BONOMO, M.; POLITIS, G. G. Mound Building, Social Complexity and Horticulture in the Lower Paraná. In: SMITH, C. (Org.) Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. New York: Springer, 2018. p. 1-22.

Indigenous architecture in the contemporary world

Indigenous architecture in the contemporary world

Like their Brazilian counterparts, Australia’s original inhabitants constructed a wide-array of building types suited to specific seasonal, environmental conditions, as well as purposes – hunting camps, windbreaks, community dining camps, etc. Equally essential, but often more difficult to understand for those outside the communities, are the cultural and conceptual importance associated with the specific design and compartmentalization of spaces. Like the sociality and openness, we associate with our living rooms, the expected privacy of our bedrooms, the functionality of the kitchen, or the storage of goods in the attic, indigenous architectural spaces are also designed and used in psychologically significant ways.

As the country of Australia’s people and its government attempt to redress or incorporate First Nations people into their national development plans, it is becoming apparent for the first time that buildings must be designed with their aboriginal ideas in mind if they are to be successful in serving those communities. The recognition creates a fascinating opportunity for the cultural principles of the use of space to re-emerge into the public spaces, housing, healthcare facilities and overall design of contemporary Australia. It is both a major challenge of building understanding across cultural divides after centuries of mistrust and exploitation.

In this Kununurra housing complex, the buildings incorporate external living areas (Photo: Peter Bennetts) From: The Handbook of Contemporary Indigenous Architecture.

Sources:

GRANT, E.; GREENOP, K.; REFITI, A.; GLEEN, D. (eds.) The Handbook of Contemporary Indigenous Architecture. New York: Springer, 2018.

Indigenous architecture in the contemporary world

Like their Brazilian counterparts, Australia’s original inhabitants constructed a wide-array of building types suited to specific seasonal, environmental conditions, as well as purposes – hunting camps, windbreaks, community dining camps, etc. Equally essential, but often more difficult to understand for those outside the communities, are the cultural and conceptual importance associated with the specific design and compartmentalization of spaces. Like the sociality and openness, we associate with our living rooms, the expected privacy of our bedrooms, the functionality of the kitchen, or the storage of goods in the attic, indigenous architectural spaces are also designed and used in psychologically significant ways.

As the country of Australia’s people and its government attempt to redress or incorporate First Nations people into their national development plans, it is becoming apparent for the first time that buildings must be designed with their aboriginal ideas in mind if they are to be successful in serving those communities. The recognition creates a fascinating opportunity for the cultural principles of the use of space to re-emerge into the public spaces, housing, healthcare facilities and overall design of contemporary Australia. It is both a major challenge of building understanding across cultural divides after centuries of mistrust and exploitation.

In this Kununurra housing complex, the buildings incorporate external living areas (Photo: Peter Bennetts) From: The Handbook of Contemporary Indigenous Architecture.

Sources:

GRANT, E.; GREENOP, K.; REFITI, A.; GLEEN, D. (eds.) The Handbook of Contemporary Indigenous Architecture. New York: Springer, 2018.

Fire:

Ignition

Ignition

What we call “fire” is the visible aspect of a combustion that releases heat and light. Fire may appear as a flame and/or coal, depending on the physical state of the combustible material. There are four conditions for fire to develop and to burn: flammable substance, oxygen, and the minimum combustion temperature, as well as the correct proportions of a flammable substance with oxygen.

The making of fire is one of the most important cultural techniques. Production and controlling fire, skills proven for approximately 80,000 years, represents a very important factor in human evolution and is an essential part of all civilizations. Fire offers warmth, light and protection from predators and insects. Its conservation socializes, adjusts the time and allows the mind to wander. Fire also cooks or roasts food, which facilitates digestion. In addition, smoked or dried food can be better preserved. Heating food also reduces its exposure to pathogenic parasites, bacteria, and viruses, making life safer and healthier. Fire makes it possible to harden wood, stone, clay to make pottery and to melt metals. The importance of fire to humanity is expressed in several mythological accounts that associate fire and its possession to supernatural and superhuman powers.

Smoke in the forest and fire in the sky. Slash and burn agriculture among the Waurá. (Photo: Harald Schultz).

Ignition

What we call “fire” is the visible aspect of a combustion that releases heat and light. Fire may appear as a flame and/or coal, depending on the physical state of the combustible material. There are four conditions for fire to develop and to burn: flammable substance, oxygen, and the minimum combustion temperature, as well as the correct proportions of a flammable substance with oxygen.

The making of fire is one of the most important cultural techniques. Production and controlling fire, skills proven for approximately 80,000 years, represents a very important factor in human evolution and is an essential part of all civilizations. Fire offers warmth, light and protection from predators and insects. Its conservation socializes, adjusts the time and allows the mind to wander. Fire also cooks or roasts food, which facilitates digestion. In addition, smoked or dried food can be better preserved. Heating food also reduces its exposure to pathogenic parasites, bacteria, and viruses, making life safer and healthier. Fire makes it possible to harden wood, stone, clay to make pottery and to melt metals. The importance of fire to humanity is expressed in several mythological accounts that associate fire and its possession to supernatural and superhuman powers.

Smoke in the forest and fire in the sky. Slash and burn agriculture among the Waurá. (Photo: Harald Schultz).

The mythological origins of fire

The mythological origins of fire

How was the existence of fire and smoke explained and related by native Brazilian people? It depends very much on the ethnic group. Fire was used, but it did not ‘belong’ to people. Fire itself was not given to them by someone but had to be conquered or stolen from its owners with audacity and with a little help from some friends such as children, a frog, or a guinea pig.

During the day, the sun was there for all, but fire was always hidden somewhere: in someone’s body, inside some stones or inside the trees. For the Taulipáng people, for example, fire was hidden inside an old woman’s guts. One day she let it out with a loud fart when she bowed down to pick up some wood. This way she lit a fire and made a lot of manioc bread. A little girl, who saw this, told it to her people. Therefore, they came to the women to ask her for some fire to bake their own bread. When she denied it, they tied her up by hands and feet and hard-pressed her belly. Instead of fire, she defected stones that, by hitting them one against another, people now could make their own fire.

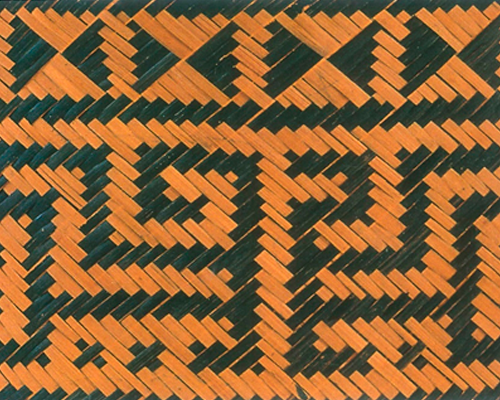

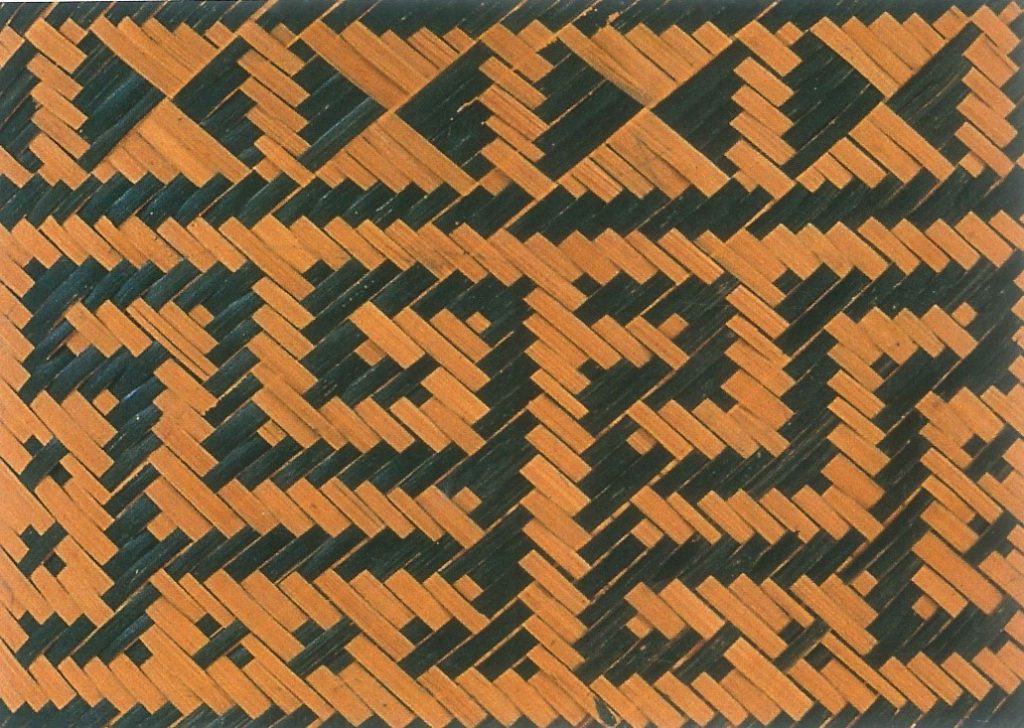

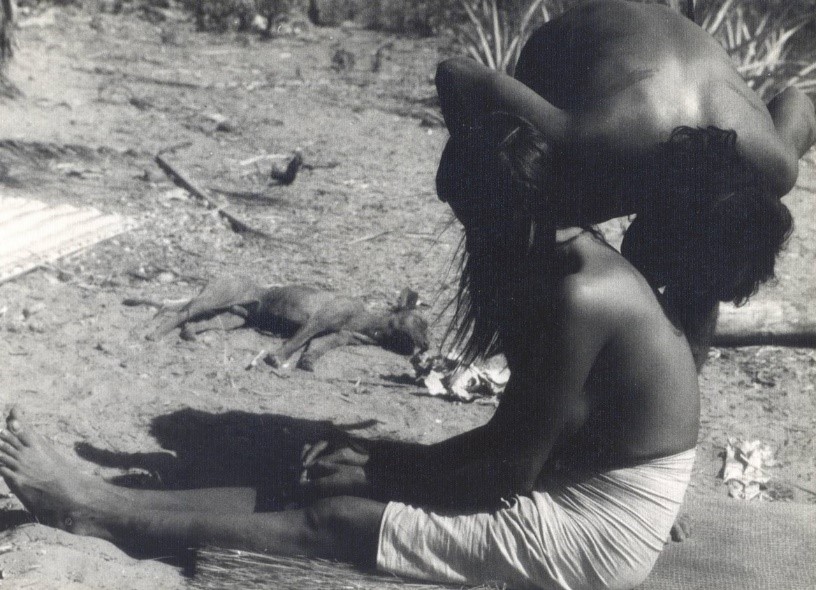

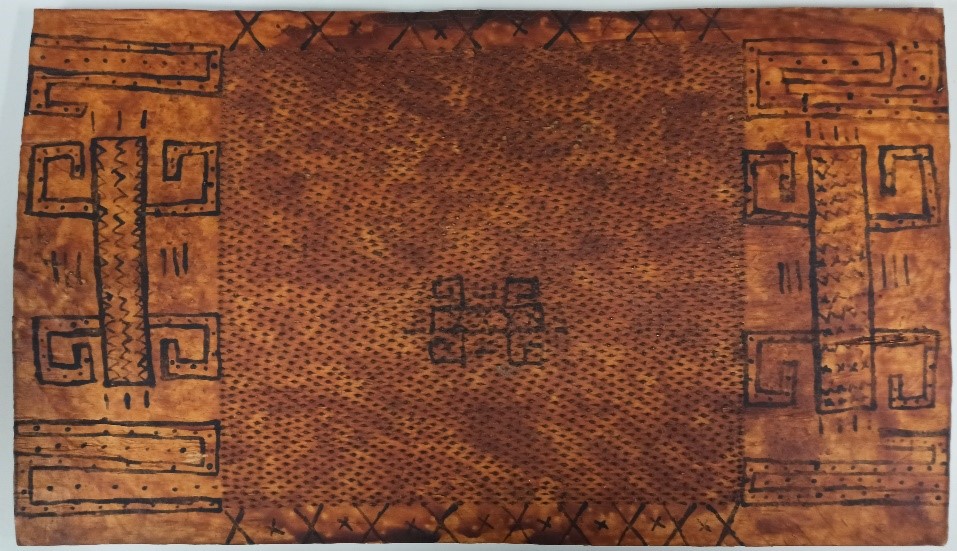

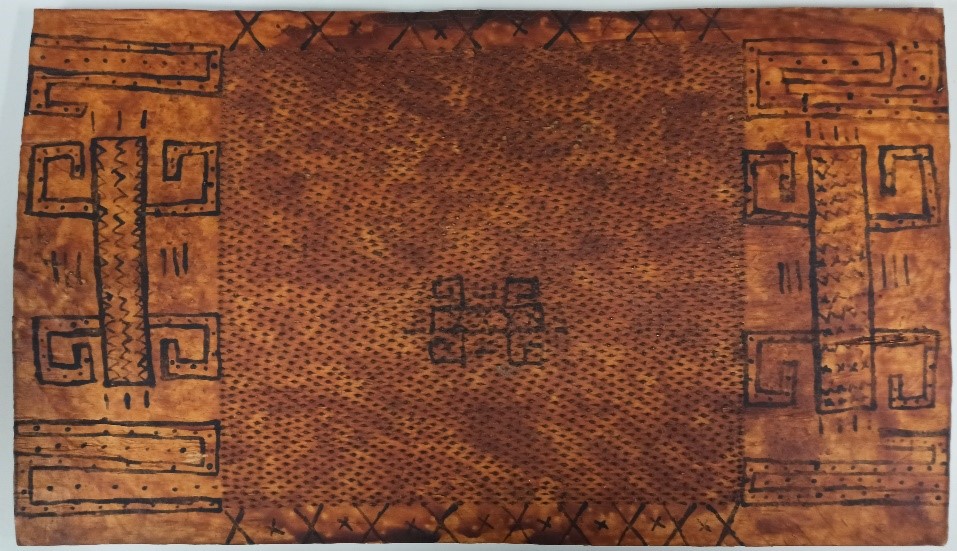

Detail of a carrying basket representing, in the Wayana drawing-pattern, some mythological owners of fire: A jaguar (right), coati and birds (at the top). (Velthem, 2001).

Sources:

KOCH-GRÜNBERG, Theodor.Vom Roraima zum Orinoco. Ergebnisse einer Reise in Nordbrasilien und Venezuela in den Jahren 1911-1913. 2.ed. Stuttgart: Strecker und Schröder. 3.v. 1923.

NIMUENDAJÚ, Curt. Sagen der Tembé-Indianer (Pará und Maranhão). Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 47:281-301. 1915.

VELTHEM, Lucia van. The woven Universe: Carib Basketry. In: McEWAN, C.; BARRETO, Ch.; NEVES, E. G. 1 Unknown Amazon. Cultured in Nature in Ancient Brazil. London: The British Museum Press, 2001, p. 198-213.

The mythological origins of fire

How was the existence of fire and smoke explained and related by native Brazilian people? It depends very much on the ethnic group. Fire was used, but it did not ‘belong’ to people. Fire itself was not given to them by someone but had to be conquered or stolen from its owners with audacity and with a little help from some friends such as children, a frog, or a guinea pig.

During the day, the sun was there for all, but fire was always hidden somewhere: in someone’s body, inside some stones or inside the trees. For the Taulipáng people, for example, fire was hidden inside an old woman’s guts. One day she let it out with a loud fart when she bowed down to pick up some wood. This way she lit a fire and made a lot of manioc bread. A little girl, who saw this, told it to her people. Therefore, they came to the women to ask her for some fire to bake their own bread. When she denied it, they tied her up by hands and feet and hard-pressed her belly. Instead of fire, she defected stones that, by hitting them one against another, people now could make their own fire.

Detail of a carrying basket representing, in the Wayana drawing-pattern, some mythological owners of fire: A jaguar (right), coati and birds (at the top). (Velthem, 2001).

Sources:

KOCH-GRÜNBERG, Theodor.Vom Roraima zum Orinoco. Ergebnisse einer Reise in Nordbrasilien und Venezuela in den Jahren 1911-1913. 2.ed. Stuttgart: Strecker und Schröder. 3.v. 1923.

NIMUENDAJÚ, Curt. Sagen der Tembé-Indianer (Pará und Maranhão). Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 47:281-301. 1915.

VELTHEM, Lucia van. The woven Universe: Carib Basketry. In: McEWAN, C.; BARRETO, Ch.; NEVES, E. G. 1 Unknown Amazon. Cultured in Nature in Ancient Brazil. London: The British Museum Press, 2001, p. 198-213.

Mythological owners of fire

Mythological owners of fire

Big birds, such as vultures or harpies, also owned fire. That is why they are so powerful. The mythological connection to fire is a cause-and-effect relation and builds up a sequence of associated signs. When there is fire, there is smoke. When there is smoke, there is heat that causes thermal winds and a band of vultures circulating in the air, and when there are vultures, there are dead animals, killed by fire. Like vultures, circulating in the hot air above the smoke and the wood burning below, Tembé people learned how to release the fire hidden in certain trees by whirling two wooden sticks against another Hans Staden, a German soldier observed in 1552 this technique among the Tupinambá when he lived among them for almost a year.

Sources:

STADEN, Hans. Duas viagens ao Brasil. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia, 1974.

Mythological owners of fire

Big birds, such as vultures or harpies, also owned fire. That is why they are so powerful. The mythological connection to fire is a cause-and-effect relation and builds up a sequence of associated signs. When there is fire, there is smoke. When there is smoke, there is heat that causes thermal winds and a band of vultures circulating in the air, and when there are vultures, there are dead animals, killed by fire. Like vultures, circulating in the hot air above the smoke and the wood burning below, Tembé people learned how to release the fire hidden in certain trees by whirling two wooden sticks against another Hans Staden, a German soldier observed in 1552 this technique among the Tupinambá when he lived among them for almost a year.

Sources:

STADEN, Hans. Duas viagens ao Brasil. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia, 1974.

Fire as a sign

Fire as a sign

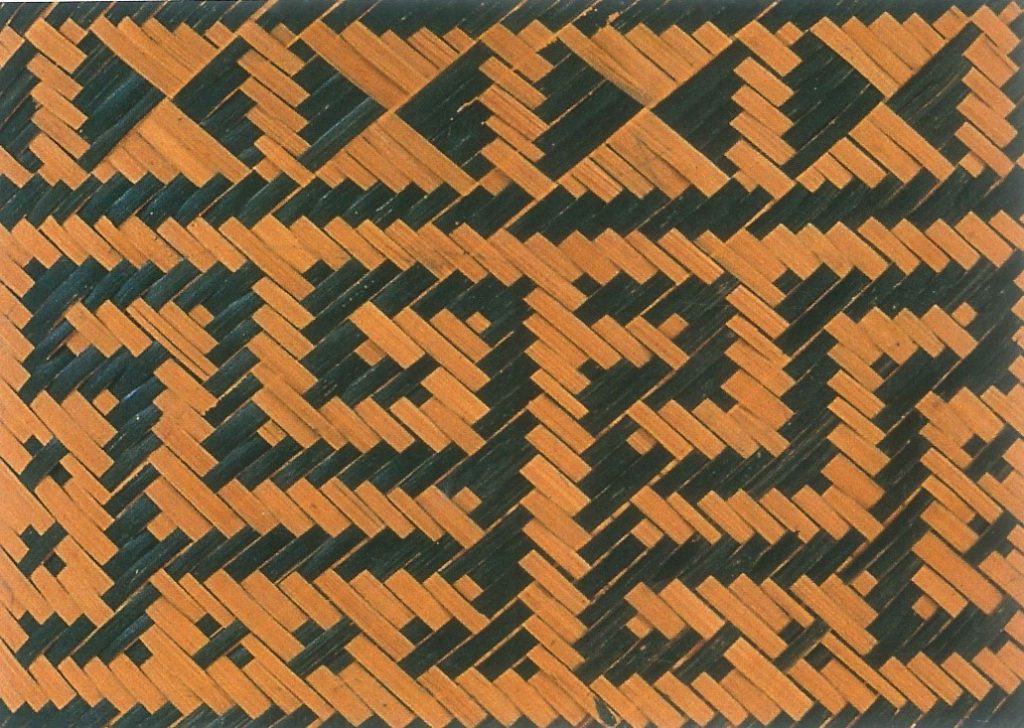

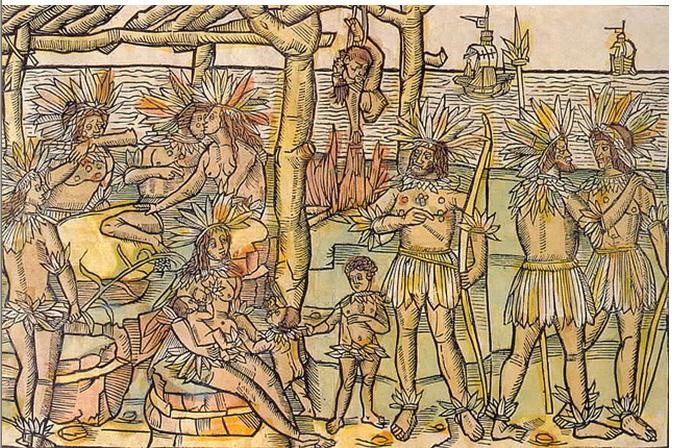

When Florentine explorer Amerigo Vespucci explored the Brazilian coast in 1501, he wrote: We did not see any people, but they were everywhere, because I saw sign all over in the woods. They make these signs of smoke to invite us to come on land to talk to us and to exchange presents. Two of our men went with them to see what they wanted to show us and were never seen again. They were selected to be part of an anthropophagical ritual that Vespucci said to have seen with his proper eyes some years later. He associated smoke, fire, and cannibalism, as illustrated by Johann Froschauer (1505), and this simplistic image of the Native Brazilian population stuck for centuries.

Sources:

VESPÚCIO, Américo. Novo Mundo. Cartas de viagens e descobertas. Porto Alegre: L&PM Editores, 1984.

Fire as a sign

When Florentine explorer Amerigo Vespucci explored the Brazilian coast in 1501, he wrote: We did not see any people, but they were everywhere, because I saw sign all over in the woods. They make these signs of smoke to invite us to come on land to talk to us and to exchange presents. Two of our men went with them to see what they wanted to show us and were never seen again. They were selected to be part of an anthropophagical ritual that Vespucci said to have seen with his proper eyes some years later. He associated smoke, fire, and cannibalism, as illustrated by Johann Froschauer (1505), and this simplistic image of the Native Brazilian population stuck for centuries.

Sources:

VESPÚCIO, Américo. Novo Mundo. Cartas de viagens e descobertas. Porto Alegre: L&PM Editores, 1984.

Domesticated fire

Domesticated fire

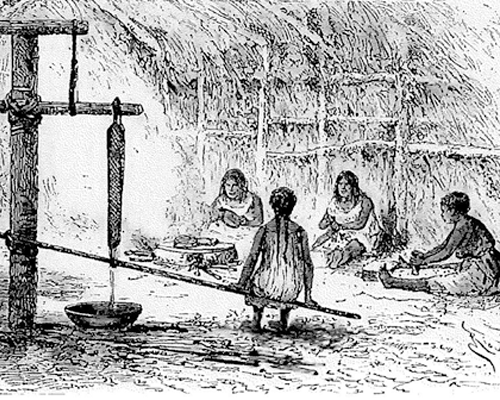

Fire can also be conceived of as an object. When it is maintained and used by people, it becomes a powerful and helpful tool. Inside people’s houses, there are many places where fire is kept domesticated and fed with wood that women bring in from outside. No indigenous household subsists without fire, and it is preserved day and night inside their houses. Some big trunks of wood are arranged in a way that the burning or smoldering ends were put together, one against each other, in a star shape. To keep the fire burning even for days, one only needs to rearrange them from time to time, placing the trunks closer together and towards the center of the gloomy fire. If the fire goes out, one simply fetches a fire from the neighbor, as usual.

Fire is kept inside the houses as a domesticated tool for cooking, grilling and smoking food. (Garmelo ; Baré, 2009).

Domesticated fire

Fire can also be conceived of as an object. When it is maintained and used by people, it becomes a powerful and helpful tool. Inside people’s houses, there are many places where fire is kept domesticated and fed with wood that women bring in from outside. No indigenous household subsists without fire, and it is preserved day and night inside their houses. Some big trunks of wood are arranged in a way that the burning or smoldering ends were put together, one against each other, in a star shape. To keep the fire burning even for days, one only needs to rearrange them from time to time, placing the trunks closer together and towards the center of the gloomy fire. If the fire goes out, one simply fetches a fire from the neighbor, as usual.

Fire is kept inside the houses as a domesticated tool for cooking, grilling and smoking food. (Garmelo ; Baré, 2009).

Fire as an object

Fire as an object

When fire is used for clearing forest for planting and hunting, the wood is converted into heat, smoke, ashes, and charcoal, which enriches the unfertile soil, and fosters a fertile planting environment. Specialists call this soil “anthropogenic dark earth”. This man-made black soil is very fertile, releases its concentrated energy lowly, over hundreds of years nourishing the plants, corn, manioc, tobacco, peanuts, beans, pumpkin, pineapple, and so forth.

However, a clearing fire can be a dangerous energy if not applied properly, leaving a devastated land, unfit for anything, left behind. Indigenous men know how to calculate the relation between wood and fire. They know how much wood is needed to keep it alive, without becoming out of control. They cut down small trees and bushes with their polished stone axes, leaving the bigger trees standing. The branches and trees are piled up together and the heap of wood needs to dry out by the heat of the sun. Dry grasses or tinder-like mass are added to this wood heap, including the felty material from the nests of certain species of ants that catches fire easily. By blowing cautiously the flame will emerge in this controlled manner. It is very exhausting work but illustrates the care with which these societies have used yet maintained their environments for millennia.

Sources:

CARNEIRO, Robert L. 1973. Slash-and-burn cultivation among the Kuikuru and its implications for development in the Amazon basin. In: GROSS, Daniel R. (ed.). Peoples and cultures in native South America. New York, Garden City: Doubleday. p. 98-125.

SOMBROEK, W.G. 1984. Soils of the Amazon Region. In: SIOLI, Harald. (ed.). The Amazon. Limnology and Landscape Ecology of a Mighty Tropical River and its Basin. Dordrecht: Junk Publishers. p. 521-535.

Fire as an object

When fire is used for clearing forest for planting and hunting, the wood is converted into heat, smoke, ashes, and charcoal, which enriches the unfertile soil, and fosters a fertile planting environment. Specialists call this soil “anthropogenic dark earth”. This man-made black soil is very fertile, releases its concentrated energy lowly, over hundreds of years nourishing the plants, corn, manioc, tobacco, peanuts, beans, pumpkin, pineapple, and so forth.

However, a clearing fire can be a dangerous energy if not applied properly, leaving a devastated land, unfit for anything, left behind. Indigenous men know how to calculate the relation between wood and fire. They know how much wood is needed to keep it alive, without becoming out of control. They cut down small trees and bushes with their polished stone axes, leaving the bigger trees standing. The branches and trees are piled up together and the heap of wood needs to dry out by the heat of the sun. Dry grasses or tinder-like mass are added to this wood heap, including the felty material from the nests of certain species of ants that catches fire easily. By blowing cautiously the flame will emerge in this controlled manner. It is very exhausting work but illustrates the care with which these societies have used yet maintained their environments for millennia.

Sources:

CARNEIRO, Robert L. 1973. Slash-and-burn cultivation among the Kuikuru and its implications for development in the Amazon basin. In: GROSS, Daniel R. (ed.). Peoples and cultures in native South America. New York, Garden City: Doubleday. p. 98-125.

SOMBROEK, W.G. 1984. Soils of the Amazon Region. In: SIOLI, Harald. (ed.). The Amazon. Limnology and Landscape Ecology of a Mighty Tropical River and its Basin. Dordrecht: Junk Publishers. p. 521-535.

Food:

Appetizer

Appetizer

The human body requires caloric energy to sustain its functionality and these proteins, sugars, and carbohydrates can arrive in the form of fruits, plant forms, as well as other animal species, from the first, sky or sea. Though the general principle surrounding food consumption is universal, each environment affords and demands different techniques for making this process reliable and sustainable.

Beyond that, because food procurement is such a labor-intensive, often collective enterprise, it has enormous cultural and social implications. Food consumption is approached and perceived in different ways by different societies, often associated with social structures, sometimes ceremonial or ritualistic, but always with communal expectations about the “right” and “wrong” ways to eat – including taboos about what kinds of energy sources are to be considered food at all.

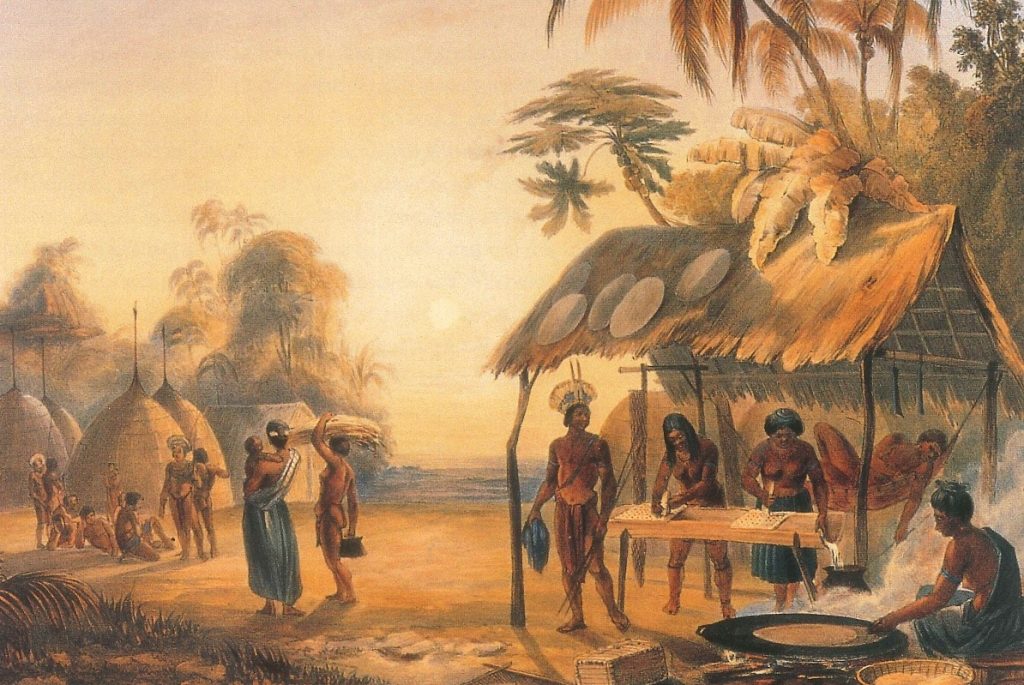

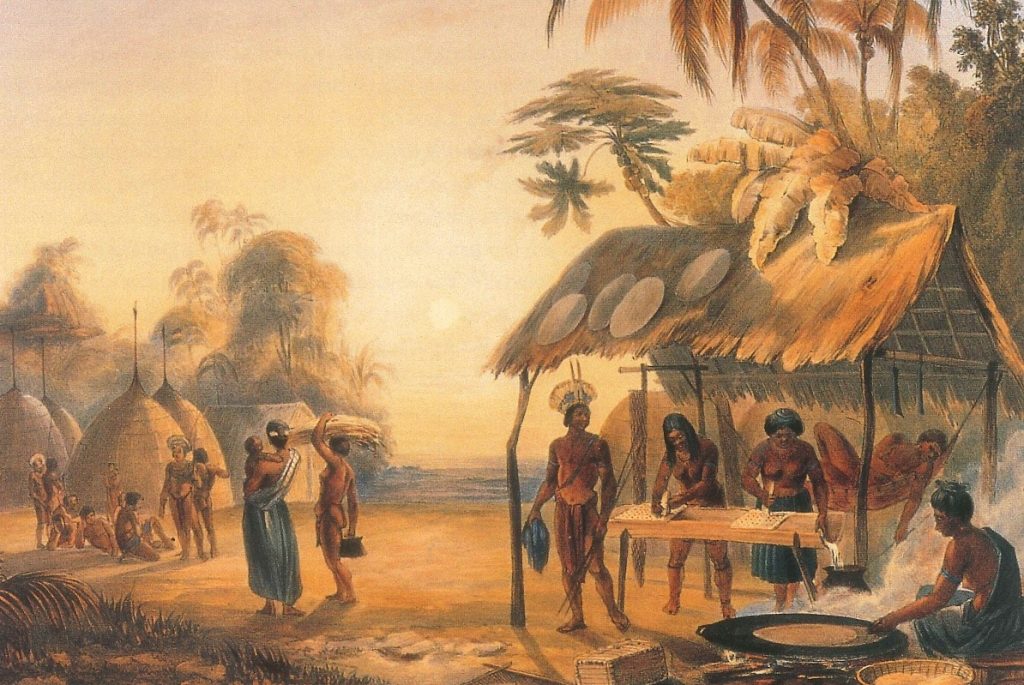

WIED-NEUWIED, M. von. Viagem ao Brasil. São Paulo: Nacional, 1958 [1815-17]

Appetizer

The human body requires caloric energy to sustain its functionality and these proteins, sugars, and carbohydrates can arrive in the form of fruits, plant forms, as well as other animal species, from the first, sky or sea. Though the general principle surrounding food consumption is universal, each environment affords and demands different techniques for making this process reliable and sustainable.

Beyond that, because food procurement is such a labor-intensive, often collective enterprise, it has enormous cultural and social implications. Food consumption is approached and perceived in different ways by different societies, often associated with social structures, sometimes ceremonial or ritualistic, but always with communal expectations about the “right” and “wrong” ways to eat – including taboos about what kinds of energy sources are to be considered food at all.

WIED-NEUWIED, M. von. Viagem ao Brasil. São Paulo: Nacional, 1958 [1815-17]

Welcoming

Welcoming

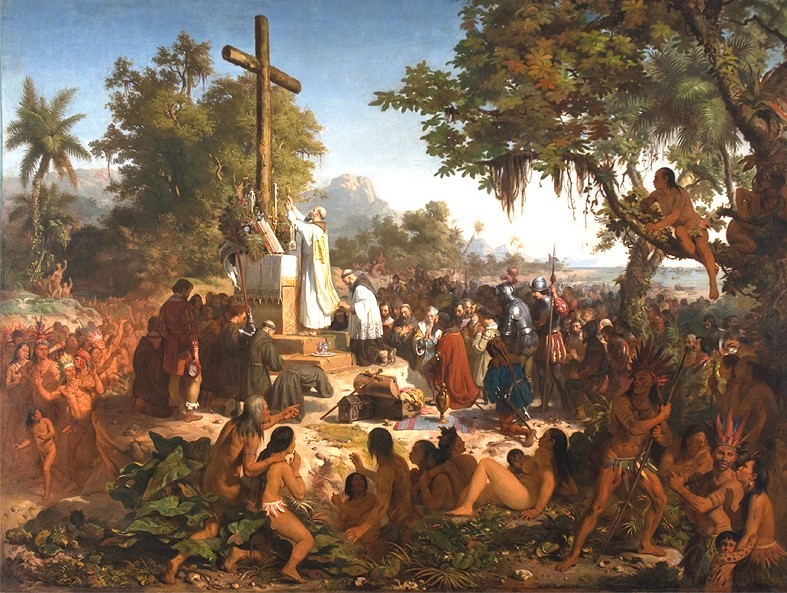

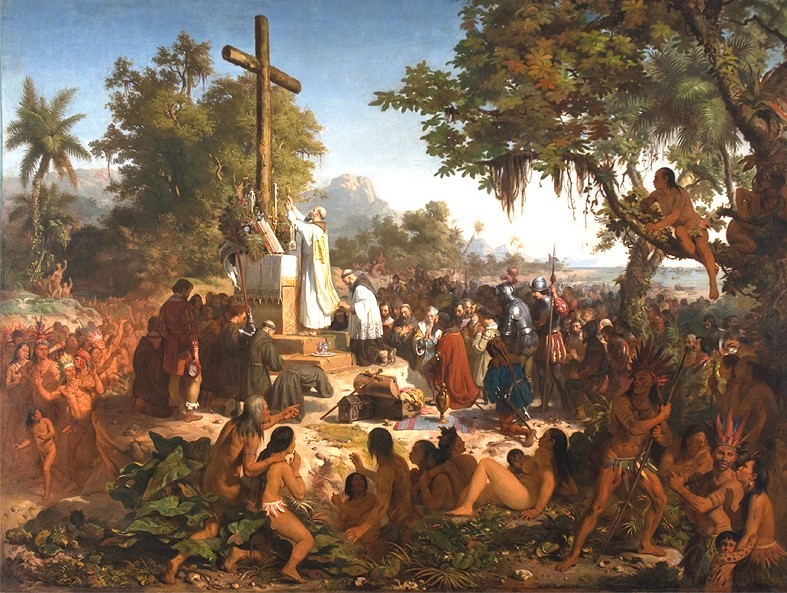

Sitting around a fire, either in or outside the home, is the central place of socialization in Brazilian indigenous societies. The fire is not only a place to stay warm, but a grill and stove to cook meals, generally in a huge pot from which anyone can serve food at any time. However, as in all societies, there are certain rules to be followed. If a stranger or even a member of his own group approaches their home as a visitor, he is allowed to enter and take a seat on a hammock. The women sit down around him in a crouched position, put their two hands in front of her faces, and begin to cry and wail, lamenting in front of the guest for the efforts and dangers of the journey he had taken to visit them and giving him all kinds of good wishes. This howling goes on until the visitor gets bored and orders the women to stop crying. Food is only brought to the guest when all this greeting ceremony has been properly fulfilled.

The first encounter between Portuguese and Tupinambá native population imagined and painted in a romantic way. The First Mass in Brazil (Victor Meirelles, 1860).

Welcoming

Sitting around a fire, either in or outside the home, is the central place of socialization in Brazilian indigenous societies. The fire is not only a place to stay warm, but a grill and stove to cook meals, generally in a huge pot from which anyone can serve food at any time. However, as in all societies, there are certain rules to be followed. If a stranger or even a member of his own group approaches their home as a visitor, he is allowed to enter and take a seat on a hammock. The women sit down around him in a crouched position, put their two hands in front of her faces, and begin to cry and wail, lamenting in front of the guest for the efforts and dangers of the journey he had taken to visit them and giving him all kinds of good wishes. This howling goes on until the visitor gets bored and orders the women to stop crying. Food is only brought to the guest when all this greeting ceremony has been properly fulfilled.

The first encounter between Portuguese and Tupinambá native population imagined and painted in a romantic way. The First Mass in Brazil (Victor Meirelles, 1860).

Eating habits

Eating habits

During the day, the Tupinambá eat lying in their hammock and all the relatives eat together. The head of the household divides the food, which he takes from a pot placed on a fire, into equal portions, and often he is left with nothing. While they eat, they do not drink, which they do afterwards. When the Tupinambá people have food at night, they sit on the ground, turning their backs to the fire and all of them have their meal in the dark. When finished, they do nothing else but digest, until sleep overcomes them.

On the contrary, the Warrau eat little at a time, but therefore more often. They eat at least five times a day. Wives are only rarely permitted to eat in company with men and this rule holds good among many indigenous people. If weather permits, the Warrau take their meal in front of the house. The wives place the dish on the ground, close by, on a sort of plate made of interwoven palm leaves. After they have withdrawn, the men, cowering on their heels, gather themselves around the steaming pot, steep the bits of cassava-bread into the stew and try, with the help of their fingers, to pick the meat from out of the vessel. As soon as their hunger is satisfied, the men leave the circle. When the last male member has “left the table,” the women approach and must be content with what is left. But they nevertheless know how to secure themselves against hunger and accordingly make sure, by means of a lot of little pots which, filled with goodies, are hidden away in all corners of the house, and, after the men have retired, afford them a more abundant meal.

Sources:

SCHOMBURGK, R. Twelve Views in the Interior of Guiana. London: Ackermann & Co.1841.

SOUSA, G. S. de. Tratado descriptivo do Brasil: em 1587: São Paulo: Editora Nacional, 1938.

Eating habits

During the day, the Tupinambá eat lying in their hammock and all the relatives eat together. The head of the household divides the food, which he takes from a pot placed on a fire, into equal portions, and often he is left with nothing. While they eat, they do not drink, which they do afterwards. When the Tupinambá people have food at night, they sit on the ground, turning their backs to the fire and all of them have their meal in the dark. When finished, they do nothing else but digest, until sleep overcomes them.

On the contrary, the Warrau eat little at a time, but therefore more often. They eat at least five times a day. Wives are only rarely permitted to eat in company with men and this rule holds good among many indigenous people. If weather permits, the Warrau take their meal in front of the house. The wives place the dish on the ground, close by, on a sort of plate made of interwoven palm leaves. After they have withdrawn, the men, cowering on their heels, gather themselves around the steaming pot, steep the bits of cassava-bread into the stew and try, with the help of their fingers, to pick the meat from out of the vessel. As soon as their hunger is satisfied, the men leave the circle. When the last male member has “left the table,” the women approach and must be content with what is left. But they nevertheless know how to secure themselves against hunger and accordingly make sure, by means of a lot of little pots which, filled with goodies, are hidden away in all corners of the house, and, after the men have retired, afford them a more abundant meal.

Sources:

SCHOMBURGK, R. Twelve Views in the Interior of Guiana. London: Ackermann & Co.1841.

SOUSA, G. S. de. Tratado descriptivo do Brasil: em 1587: São Paulo: Editora Nacional, 1938.

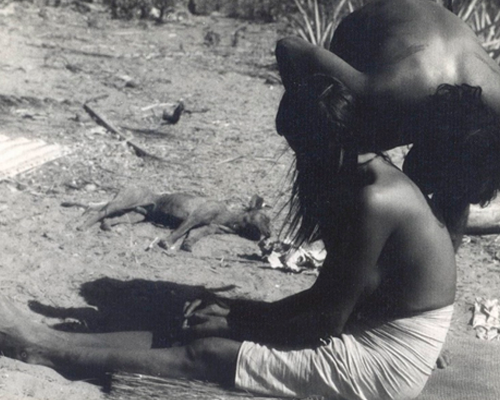

Gender roles and food preparation

Gender roles and food preparation

There is a strict division of labor between the two sexes. The man fries, while the woman cooks the food. Only very rarely and reluctantly will a man do the female work, and vice versa. The basic food of indigenous population includes both animal and vegetable stuff. Men provide animals, by hunting and fishing, while women, almost unassisted, provide the latter.

The hunters, after returning from a few days’ journey into the forest, smoke the meat on a barbecue-grill or by salting the fish. A fire, that is not too strong, is kept under the grill day and night until the meat has become completely black and bone-hard, so that one sometimes must cut it apart with an ax, and then cook the individual pieces to make them more palatable. These are the rough processes, which are not the final cooking of the meat but are only meant to preserve it until it can be handed over to the women at home. As regards the meat, which the men consume during these hunting and fishing excursions, the method of preparing this is extremely simple. The meat is indeed often eaten just in the half-roasted, half-smoked state in which it is taken off the grill; or, at most, it is cut into small bits, which are fastened into a cleft stick and so held or fastened over the fire until they are roasted. All other cooking, not only of the dried meat brought home and of meat procured near enough to the settlement to be cooked while fresh, but also of cassava-bread, the only staple vegetable consumed, is done by the women.

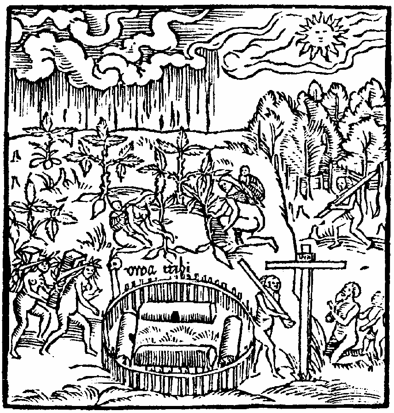

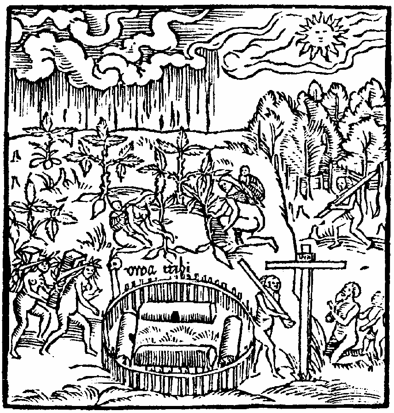

Illustration of Tupinambá women planting and the men cutting the forest. (Staden, 1974).

Sources

KOCH-GRÜNBERG, Theodor. Zwei Jahre unter den Indianern Nordwest-Brasiliens. Stuttgart: Strecker & Schröder, 1923.

STADEN, Hans. Duas viagens ao Brasil. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia, 1974, [1557].

Gender roles and food preparation

There is a strict division of labor between the two sexes. The man fries, while the woman cooks the food. Only very rarely and reluctantly will a man do the female work, and vice versa. The basic food of indigenous population includes both animal and vegetable stuff. Men provide animals, by hunting and fishing, while women, almost unassisted, provide the latter.

The hunters, after returning from a few days’ journey into the forest, smoke the meat on a barbecue-grill or by salting the fish. A fire, that is not too strong, is kept under the grill day and night until the meat has become completely black and bone-hard, so that one sometimes must cut it apart with an ax, and then cook the individual pieces to make them more palatable. These are the rough processes, which are not the final cooking of the meat but are only meant to preserve it until it can be handed over to the women at home. As regards the meat, which the men consume during these hunting and fishing excursions, the method of preparing this is extremely simple. The meat is indeed often eaten just in the half-roasted, half-smoked state in which it is taken off the grill; or, at most, it is cut into small bits, which are fastened into a cleft stick and so held or fastened over the fire until they are roasted. All other cooking, not only of the dried meat brought home and of meat procured near enough to the settlement to be cooked while fresh, but also of cassava-bread, the only staple vegetable consumed, is done by the women.

Illustration of Tupinambá women planting and the men cutting the forest. (Staden, 1974).

Sources

KOCH-GRÜNBERG, Theodor. Zwei Jahre unter den Indianern Nordwest-Brasiliens. Stuttgart: Strecker & Schröder, 1923.

STADEN, Hans. Duas viagens ao Brasil. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia, 1974, [1557].

Cooking - (The Pepper-pot)

Cooking - (The Pepper-pot)

Cooking is perhaps the most frequent occupation of women. In general, indigenous people do not eat at regular times, but whenever and as often as they feel inclined. The pepper-pot method and cassava-bread invariably form the meal. All the meat or fish obtained is put into the pot together with cassareep and peppers (capsicum) and boiled into a thick soup. This pot is never cleaned or emptied, but more meat is added whenever necessary. This soup is boiled again and again and is ready for consumption at any time. A store of cassava-bread is also at hand whenever required; for large quantities are made at each baking. The pepper as an ingredient, has antiseptic qualities which keep meat boiled in it for a long time. Whenever the men feel hungry, the women bring the pepper-pot, with some boiled cassava roots served on one of the fans which are used for blowing the fire, to the side of the hammock. The men often do not trouble themselves to get out of their hammocks, but simply lean over the sides to eat. At other times they get up and sit on one of the low wooden stools, or they bend before their food with their knees drawn up almost to their heads. This is their usual sitting position. The bread is dipped into the soup, and a sodden piece of bread is bitten off. Very little is eaten at a time; and when the meal is over, the men roll back into their hammocks, and the women fetch away the remains of the food.

Waurá children eating from a cooking-pot. End of the party. (Photo: Harald Schultz).

Sources:

KOCH-GRÜNBERG, Theodor. Zwei Jahre unter den Indianern Nordwest-Brasiliens. Stuttgart: Strecker & Schröder, 1923.

Cooking - (The Pepper-pot)

Cooking is perhaps the most frequent occupation of women. In general, indigenous people do not eat at regular times, but whenever and as often as they feel inclined. The pepper-pot method and cassava-bread invariably form the meal. All the meat or fish obtained is put into the pot together with cassareep and peppers (capsicum) and boiled into a thick soup. This pot is never cleaned or emptied, but more meat is added whenever necessary. This soup is boiled again and again and is ready for consumption at any time. A store of cassava-bread is also at hand whenever required; for large quantities are made at each baking. The pepper as an ingredient, has antiseptic qualities which keep meat boiled in it for a long time. Whenever the men feel hungry, the women bring the pepper-pot, with some boiled cassava roots served on one of the fans which are used for blowing the fire, to the side of the hammock. The men often do not trouble themselves to get out of their hammocks, but simply lean over the sides to eat. At other times they get up and sit on one of the low wooden stools, or they bend before their food with their knees drawn up almost to their heads. This is their usual sitting position. The bread is dipped into the soup, and a sodden piece of bread is bitten off. Very little is eaten at a time; and when the meal is over, the men roll back into their hammocks, and the women fetch away the remains of the food.

Waurá children eating from a cooking-pot. End of the party. (Photo: Harald Schultz).

Sources:

KOCH-GRÜNBERG, Theodor. Zwei Jahre unter den Indianern Nordwest-Brasiliens. Stuttgart: Strecker & Schröder, 1923.

Cassava root

Cassava root

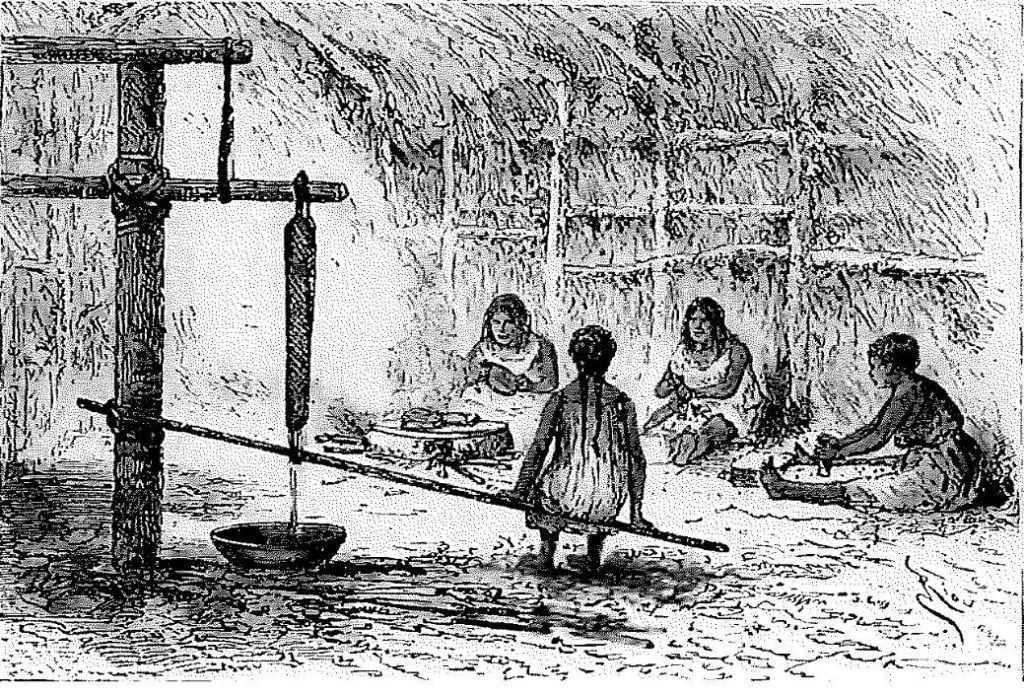

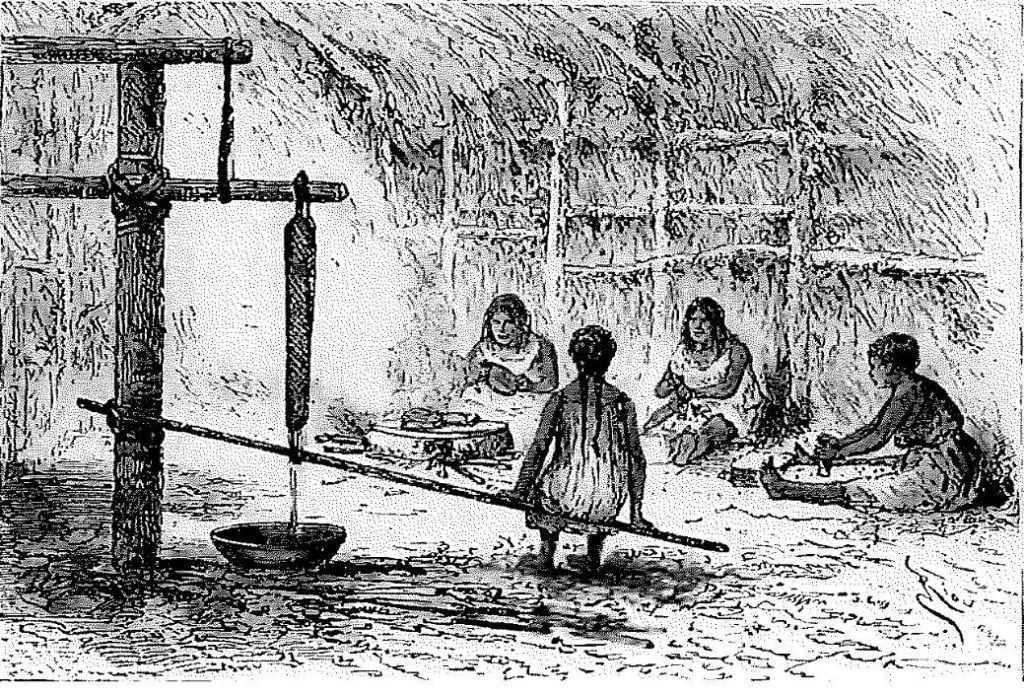

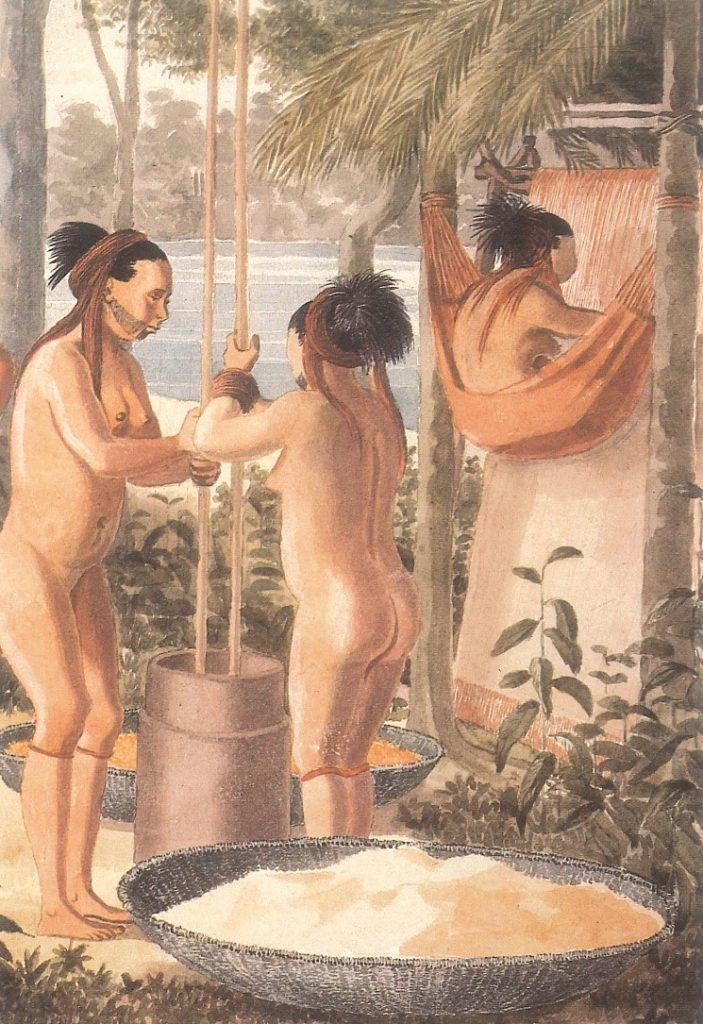

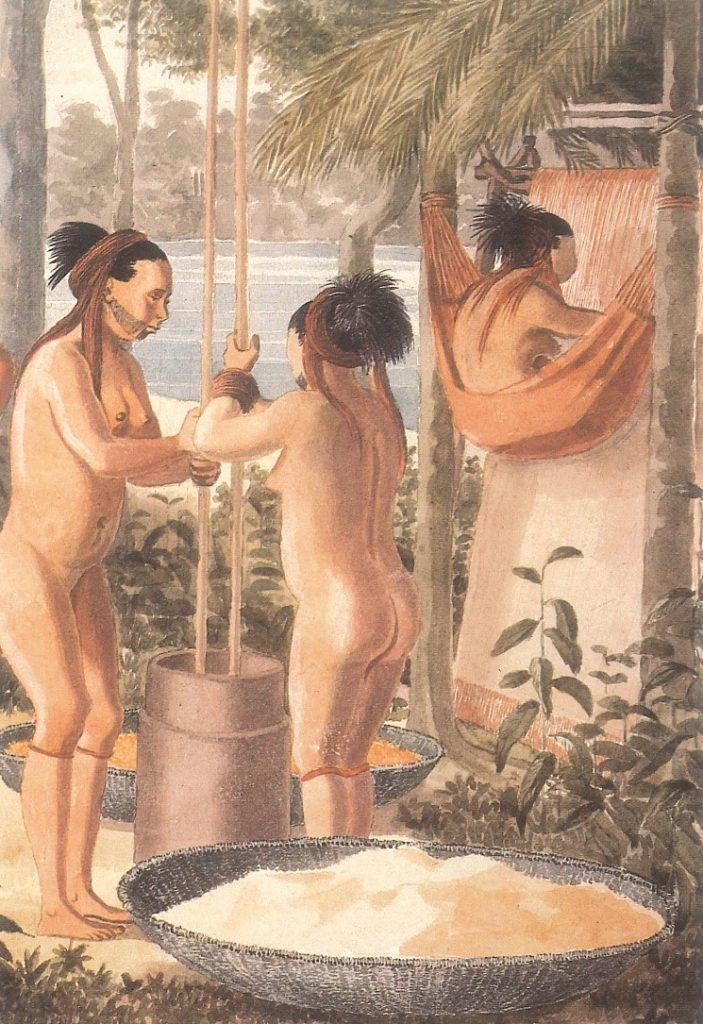

The one indispensable vegetable food of indigenous people is provided by the roots of the cassava-plant (Manihot utilissima), which are made into bread, like pancakes or into farina. No scene is more characteristic of indigenous life than that of the women preparing cassava-roots: One woman, armed with a big knife, peels off the skin of the cassava roots, which lie in a heap at her side. Each root, after being peeled, is washed, and then thrown on to a new heap. A little way off, another woman stands and, grabbing one of the peeled roots with both hands, scrapes it up and down on an oblong board or grater studded with small fragments of stone, and so roughened. One end of the greater stands in a trough on the ground, the other rests against the woman’s knees. It is a tough exercise. As the woman scrapes, her body swings down and up again from her hips. The rhythmic ‘swish’ caused by the scraping of the juicy root is the dominant sound in the house, for the work is too heavy to permit talking. The cassava root, which slips as pulp from the scraper into the trough, is collected and put into a long wicker-woven tube-like basket, called ‘tipipi’. This cassava-squeezer is a cylinder, seven or eight feet long and five or six inches in diameter, made of closely woven strips of pliant bark. The upper end is open and has a loop by which the ‘tipiti’ may be suspended from one of the beams of the house. The lower end is closed, but also has a loop. The cassava, saturated with its highly poisonous juice (hydric acid), is now squeezed into this tube-like basket through the opening at the top. A heavy pole is passed now through the loop at the lower end of the ‘tipiti’, while the other is raised and fixed on a beam of the house. A woman now sits on the raised end of the pole, and her weight stretches the cylinder downwards. The pressure thus applied to the cassava pulp immediately forces the poisonous juice out through the sides of the braided tube. The juice drops down into a pot, which stands on the ground. This juice, after it has been boiled, becomes cassareep, a thick, treacle-like liquid, which is no longer poisonous, and used in the manufacture of pepper-pot. The cassava, now dry and free from its poisoned liquid, is now taken from the ‘tipiti’, and passed through a sieve, so that it becomes a coarse flour. This either is wrapped in leaves or put away for future use or is at once made into bread.

Women processing the cassava-root: pealing, grinding, squeezing, and baking. (Crévaux, 1883).

Women processing the cassava-root: pealing, grinding, squeezing, and baking. (Crévaux, 1883).Sources:

CREVAUX, J. Voyagens dans l’Amérique du Sud. Hachette, Paris 1883.

Cassava root

The one indispensable vegetable food of indigenous people is provided by the roots of the cassava-plant (Manihot utilissima), which are made into bread, like pancakes or into farina. No scene is more characteristic of indigenous life than that of the women preparing cassava-roots: One woman, armed with a big knife, peels off the skin of the cassava roots, which lie in a heap at her side. Each root, after being peeled, is washed, and then thrown on to a new heap. A little way off, another woman stands and, grabbing one of the peeled roots with both hands, scrapes it up and down on an oblong board or grater studded with small fragments of stone, and so roughened. One end of the greater stands in a trough on the ground, the other rests against the woman’s knees. It is a tough exercise. As the woman scrapes, her body swings down and up again from her hips. The rhythmic ‘swish’ caused by the scraping of the juicy root is the dominant sound in the house, for the work is too heavy to permit talking. The cassava root, which slips as pulp from the scraper into the trough, is collected and put into a long wicker-woven tube-like basket, called ‘tipipi’. This cassava-squeezer is a cylinder, seven or eight feet long and five or six inches in diameter, made of closely woven strips of pliant bark. The upper end is open and has a loop by which the ‘tipiti’ may be suspended from one of the beams of the house. The lower end is closed, but also has a loop. The cassava, saturated with its highly poisonous juice (hydric acid), is now squeezed into this tube-like basket through the opening at the top. A heavy pole is passed now through the loop at the lower end of the ‘tipiti’, while the other is raised and fixed on a beam of the house. A woman now sits on the raised end of the pole, and her weight stretches the cylinder downwards. The pressure thus applied to the cassava pulp immediately forces the poisonous juice out through the sides of the braided tube. The juice drops down into a pot, which stands on the ground. This juice, after it has been boiled, becomes cassareep, a thick, treacle-like liquid, which is no longer poisonous, and used in the manufacture of pepper-pot. The cassava, now dry and free from its poisoned liquid, is now taken from the ‘tipiti’, and passed through a sieve, so that it becomes a coarse flour. This either is wrapped in leaves or put away for future use or is at once made into bread.

Women processing the cassava-root: pealing, grinding, squeezing, and baking. (Crévaux, 1883).

Women processing the cassava-root: pealing, grinding, squeezing, and baking. (Crévaux, 1883).Sources:

CREVAUX, J. Voyagens dans l’Amérique du Sud. Hachette, Paris 1883.

Cassava bread

Cassava bread

A large circular ceramic platter, an iron griddle or plate is now placed over the fire. On the griddle, a thin layer of the flour is spread. A woman, fan in hand, sits by the fire, watching. With her fan she smooths the upper surface of the cake rounding up its edges. In a very few minutes one side of the large round white cake is done. And when it has been turned, in yet a couple of minutes the bread is ready. When enough of these pancake-like pieces of bread have been made, they are taken out of the house and thrown up on the roof to dry in the sun. When thoroughly sun-dried the bread is hard and crisp. In this state, if protected from humidity, it will keep for an indefinite time.

Apiacá-women preparing cassava flour. (Watercolor by H. Florence, from: Langsdorff, 1988).

Sources:

LANGSDORFF, J.H von. Expedição Langsdorff no Brasil 1821-29. São Paulo: Alumbramento, 1988, v.3.

Cassava bread

A large circular ceramic platter, an iron griddle or plate is now placed over the fire. On the griddle, a thin layer of the flour is spread. A woman, fan in hand, sits by the fire, watching. With her fan she smooths the upper surface of the cake rounding up its edges. In a very few minutes one side of the large round white cake is done. And when it has been turned, in yet a couple of minutes the bread is ready. When enough of these pancake-like pieces of bread have been made, they are taken out of the house and thrown up on the roof to dry in the sun. When thoroughly sun-dried the bread is hard and crisp. In this state, if protected from humidity, it will keep for an indefinite time.

Apiacá-women preparing cassava flour. (Watercolor by H. Florence, from: Langsdorff, 1988).

Sources:

LANGSDORFF, J.H von. Expedição Langsdorff no Brasil 1821-29. São Paulo: Alumbramento, 1988, v.3.

Cassava beer

Cassava beer

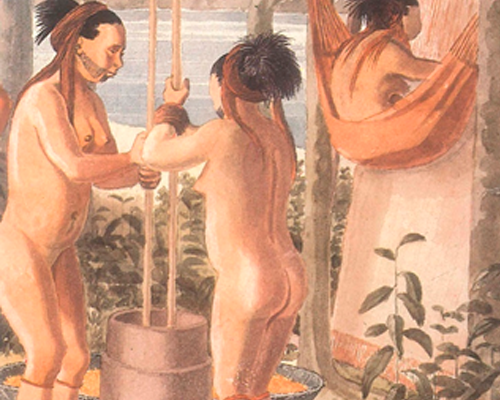

Some of the cassava, after being made into bread, is further transformed into beer or ‘cauim’ the main indigenous beverage. Cassava bread which is to be transformed into beer is thicker, and is baked, or rather burned, until it is quite black. It is then broken into small bits and mixed with water in a large jar. The larger fragments are picked out and chewed by the women, who do this work while moving about and performing their usual household work. The chewed masses are spitted back into the jar. As soon as this jar is sufficiently filled, its contents, after being well stirred, are slightly boiled, and then poured into a large pot. The mixture is then allowed to stand for some days, until it is sufficiently fermented. This process is accelerated by the mastication of the cassava bread. The result is a brownish liquor, with a slightly acidic, but not unpleasant taste.

Tupinambá-women preparing cassava bear -Cauim (Theodor DeBry. from: Hans Staden 1557)

Tupinambá-women preparing cassava bear -Cauim (Theodor DeBry. from: Hans Staden 1557)Sources:

KOCH-GRÜNBERG, Theodor. Zwei Jahre unter den Indianern Nordwest-Brasiliens. Stuttgart: Strecker & Schröder, 1923.

Cassava beer

Some of the cassava, after being made into bread, is further transformed into beer or ‘cauim’ the main indigenous beverage. Cassava bread which is to be transformed into beer is thicker, and is baked, or rather burned, until it is quite black. It is then broken into small bits and mixed with water in a large jar. The larger fragments are picked out and chewed by the women, who do this work while moving about and performing their usual household work. The chewed masses are spitted back into the jar. As soon as this jar is sufficiently filled, its contents, after being well stirred, are slightly boiled, and then poured into a large pot. The mixture is then allowed to stand for some days, until it is sufficiently fermented. This process is accelerated by the mastication of the cassava bread. The result is a brownish liquor, with a slightly acidic, but not unpleasant taste.

Tupinambá-women preparing cassava bear -Cauim (Theodor DeBry. from: Hans Staden 1557)

Tupinambá-women preparing cassava bear -Cauim (Theodor DeBry. from: Hans Staden 1557)Sources:

KOCH-GRÜNBERG, Theodor. Zwei Jahre unter den Indianern Nordwest-Brasiliens. Stuttgart: Strecker & Schröder, 1923.

Forest and trees:

Implantation

Implantation

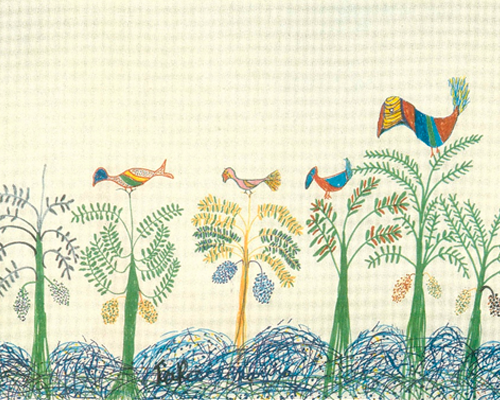

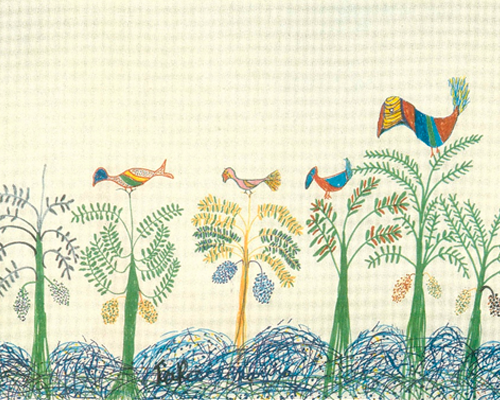

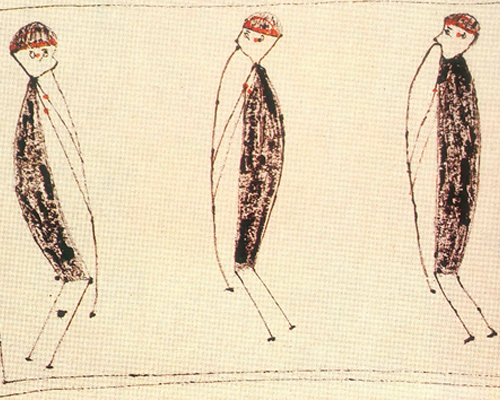

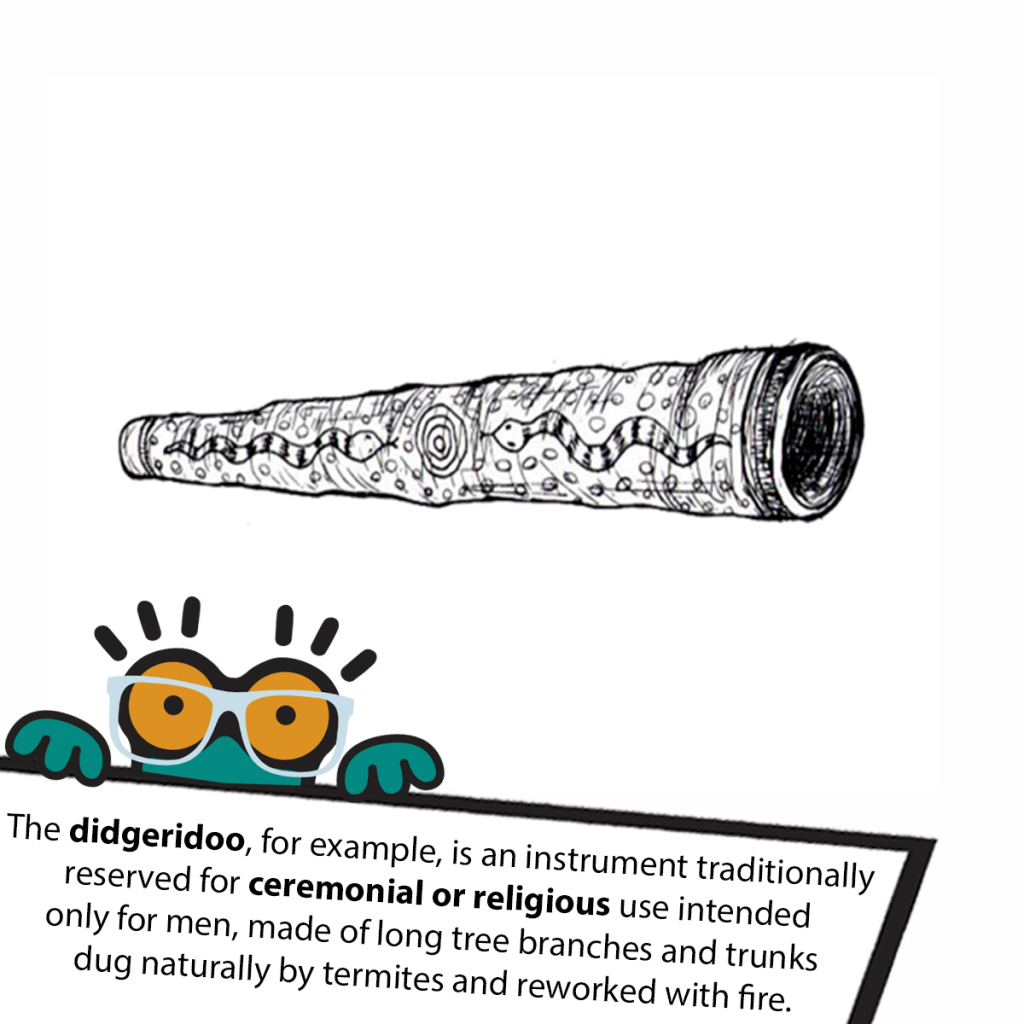

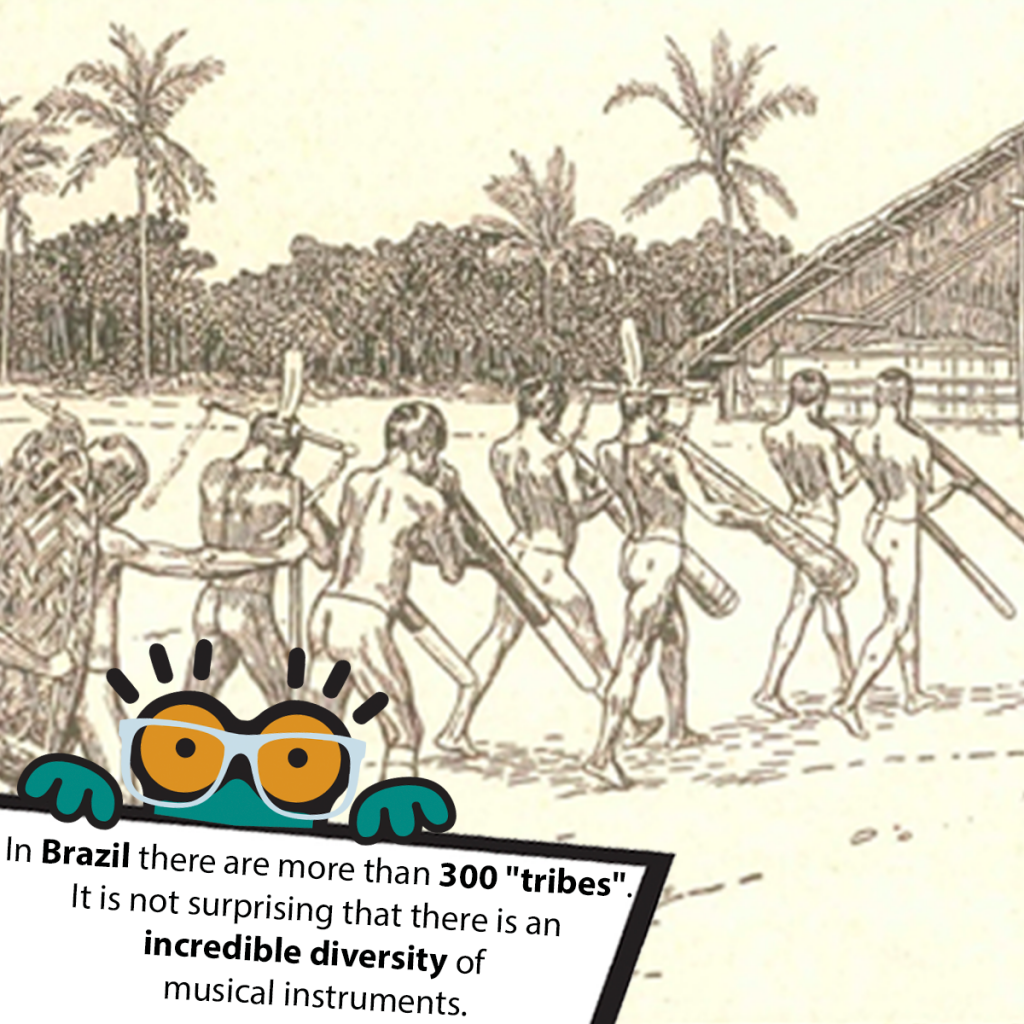

The forests of the planet have always been integral to human adaptation and survival. Not only for the obvious use of burning wood for fires, but also using leaves for medicinal remedies, seeds for protein-rich food, and trunks and barks for transportation, weapons, musical instruments, art, and clothing. For all these reasons, trees are an incomparably rich source of adaptational practices in past and present times.

Arboreal ecosystems support likewise provide the ecological niches that so many plants and animals depend on — forests are the apex of the biodiverse setting in which humans also thrive. It’s not surprising that over the span of human development many peoples have put great effort into maintaining, and often altering, forest composition for its continued use. Often times single tree species can be especially handy for a society and ends up taking on a prestigious role in the cultural life of the people as well. This is the case with the two ‘key’ tree species explored here.

The forest of the Xingu-area. Trees and birds. (Color pencil drawing by Tapayé-Waurá. From: Coelho, 1986).

Sources:

COELHO, Vera P. Die Waurá. Mythen und Zeichnungen eines brasilianischen Indianerstammes. Leipzig-Weimar: Gustav Kiepenheuer Verlag, 1986.

DENEVAN, W. M. Cultivated Landscapes of Native Amazonia and the Andes. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2005.

Implantation

The forests of the planet have always been integral to human adaptation and survival. Not only for the obvious use of burning wood for fires, but also using leaves for medicinal remedies, seeds for protein-rich food, and trunks and barks for transportation, weapons, musical instruments, art, and clothing. For all these reasons, trees are an incomparably rich source of adaptational practices in past and present times.

Arboreal ecosystems support likewise provide the ecological niches that so many plants and animals depend on — forests are the apex of the biodiverse setting in which humans also thrive. It’s not surprising that over the span of human development many peoples have put great effort into maintaining, and often altering, forest composition for its continued use. Often times single tree species can be especially handy for a society and ends up taking on a prestigious role in the cultural life of the people as well. This is the case with the two ‘key’ tree species explored here.

The forest of the Xingu-area. Trees and birds. (Color pencil drawing by Tapayé-Waurá. From: Coelho, 1986).

Sources:

COELHO, Vera P. Die Waurá. Mythen und Zeichnungen eines brasilianischen Indianerstammes. Leipzig-Weimar: Gustav Kiepenheuer Verlag, 1986.

DENEVAN, W. M. Cultivated Landscapes of Native Amazonia and the Andes. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2005.

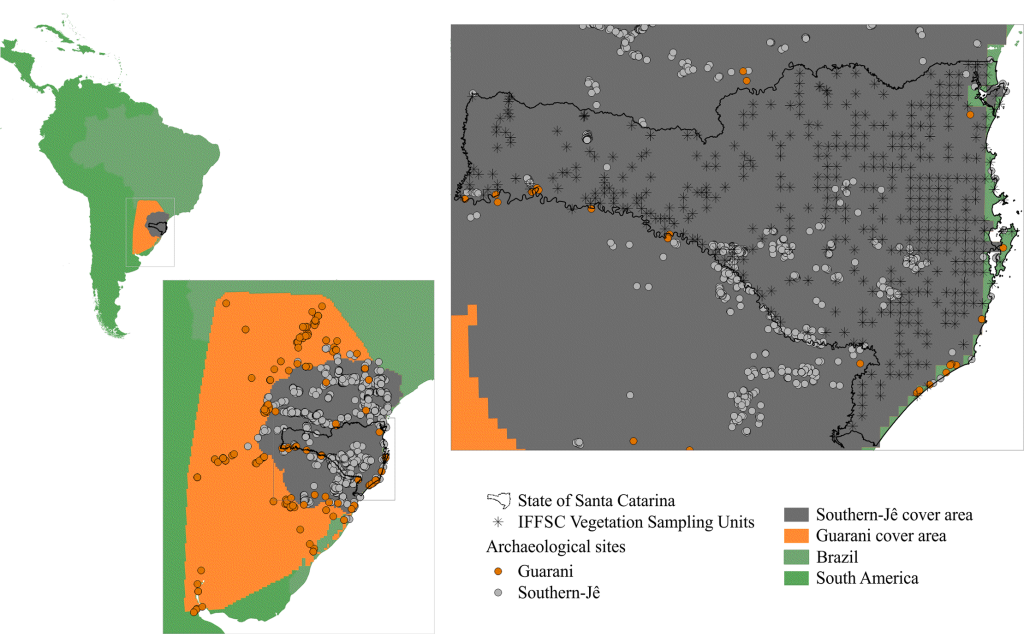

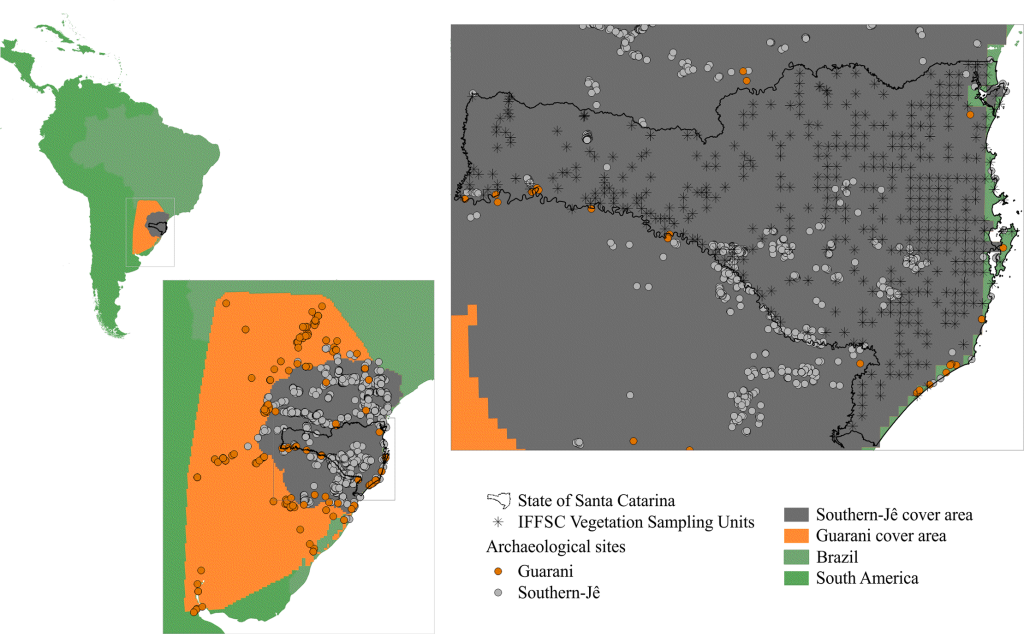

The araucaria

The araucaria

Dating all the way back to the Triassic period (think dinosaurs!), the araucaria (or to use its misleadingly moniker Brazilian pine) can today be found in Southern Brazil and parts of Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay.

Sometime in the late Holocene, just at the time archaeologists believe the indigenous societies of Brazil were heading south, the proliferation of this tree seemed to expand alongside their migration. Today we find the towns and inhabited areas of these people and cultural groups seem to overlap with the growth of the araucaria trees. This means the people and the trees were likely locked in a symbiotic relationship. But why?

Well, the araucaria is an incredible tree! Its massive pine cones which fall to the ground are full of thick, juicy pine nuts that are still sold in Brazilian supermarkets today; its branches and pine cone leaves are fantastic for starting fires; and the wood itself is easy to carve making it perfect for tools, furniture and works of art.

Today the tree is under serious threat of extinction, but new awareness of the Atlantic Forest ‘hot zone’ of biodiversity and some newly established national parks in Brazil are giving it a fighting chance. In addition, the people of southern Brazil are unlikely to give up their love of the festive, flavorful pine nuts any time soon!

The distribution of the araucaria trees seems to point to human involvement.

Sources: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0235819

CRUZ, A. P. et al. Pre-colonial Amerindian legacies in forest composition of southern Brazil. PLoS ONE. v. 15, n. 7, 2020. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235819

The araucaria

Dating all the way back to the Triassic period (think dinosaurs!), the araucaria (or to use its misleadingly moniker Brazilian pine) can today be found in Southern Brazil and parts of Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay.

Sometime in the late Holocene, just at the time archaeologists believe the indigenous societies of Brazil were heading south, the proliferation of this tree seemed to expand alongside their migration. Today we find the towns and inhabited areas of these people and cultural groups seem to overlap with the growth of the araucaria trees. This means the people and the trees were likely locked in a symbiotic relationship. But why?

Well, the araucaria is an incredible tree! Its massive pine cones which fall to the ground are full of thick, juicy pine nuts that are still sold in Brazilian supermarkets today; its branches and pine cone leaves are fantastic for starting fires; and the wood itself is easy to carve making it perfect for tools, furniture and works of art.

Today the tree is under serious threat of extinction, but new awareness of the Atlantic Forest ‘hot zone’ of biodiversity and some newly established national parks in Brazil are giving it a fighting chance. In addition, the people of southern Brazil are unlikely to give up their love of the festive, flavorful pine nuts any time soon!

The distribution of the araucaria trees seems to point to human involvement.

Sources: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0235819

CRUZ, A. P. et al. Pre-colonial Amerindian legacies in forest composition of southern Brazil. PLoS ONE. v. 15, n. 7, 2020. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235819

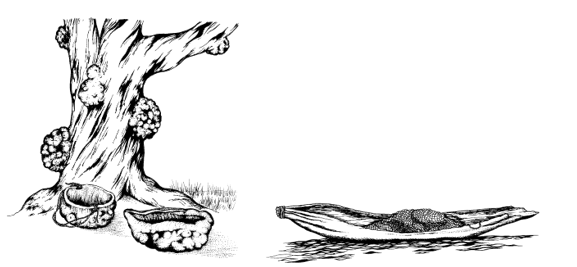

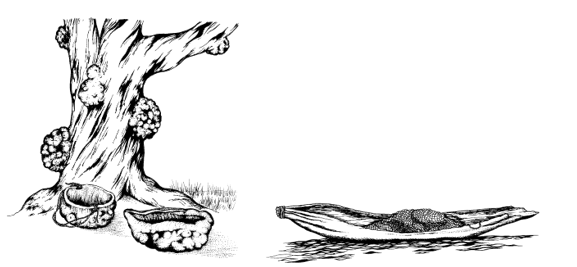

The eucalyptus

The eucalyptus

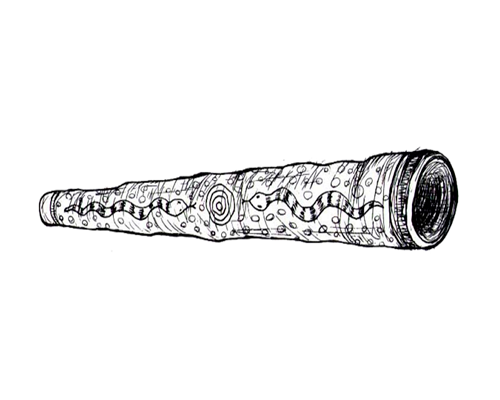

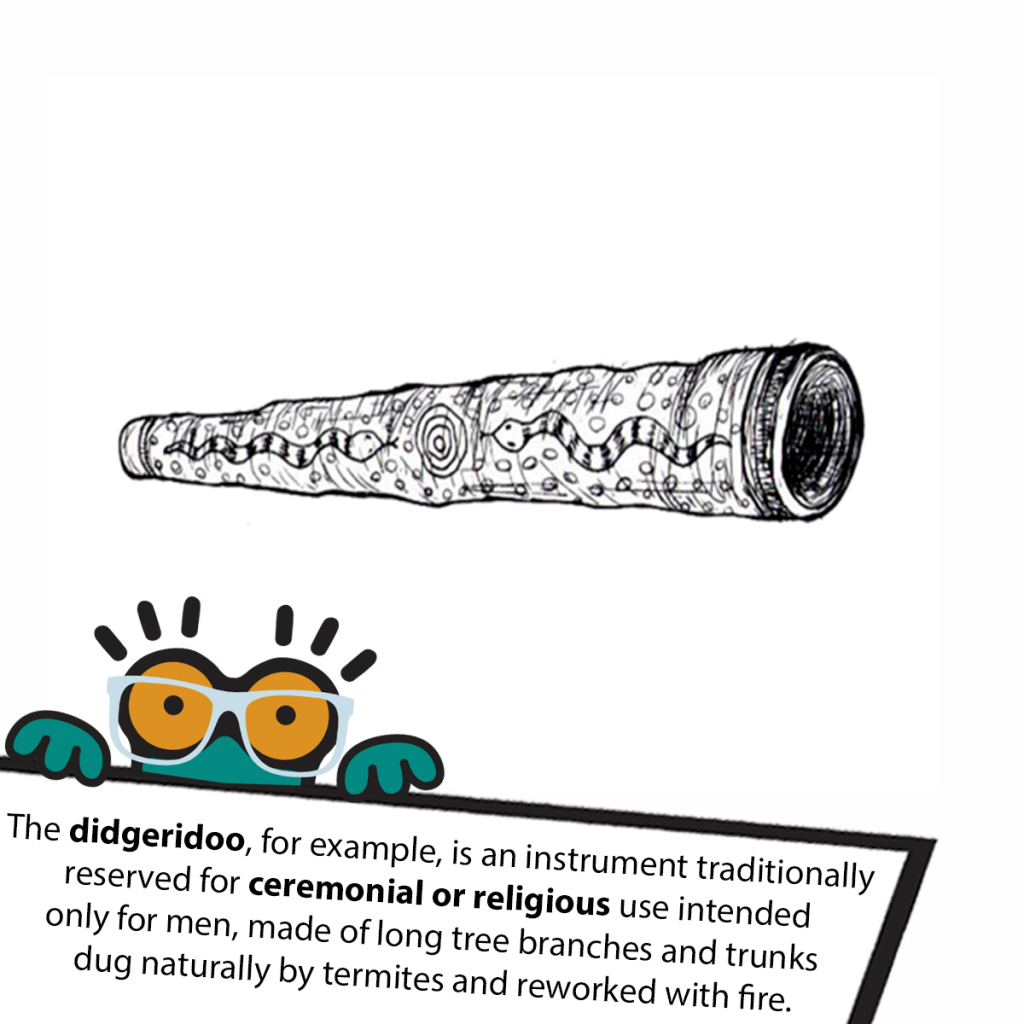

The eucalyptus has long been Australia’s most important tree for human use. It’s no surprise, since about two-thirds of the forests in Australia are eucalyptus forests and given the tree’s incredible versatility.

Of course, the eucalyptus’ most cuddly fan is the koala, but indigenous societies, in the past and today, have found many, many uses for this beautiful tree. For one, they invented a technique for using long strips of tree’s bark to make impressive and very strong canoes for navigating the rivers. The wood itself is great for drinking vessels, musical instruments, spear-throwers, shields, and, of course, boomerangs! Aside from this, the leaves, which are famously fragrant, have medicinal and therapeutic properties helping people globally. Their oil has also proven effective as a naturally based insecticide.

Today, you can find species of eucalyptus around the globe in appropriate climates. In California they were planted by the tens of thousands to create massive windbreaks to protect the agricultural sector that has since gone on to feed billions. The beauty and utility of the eucalyptus is timeless but does stand at the risk of increasingly destructive wildfires in Australia, California, and elsewhere.

Drinking vessels and sturdy canoes are just a few of the indigenous inventions that make use of the eucalyptus tree. Sources: Australia National Botanic Gardens.

Sources:

Australia National Botanic Gardens, website: https://anbg.gov.au/index.html

The eucalyptus

The eucalyptus has long been Australia’s most important tree for human use. It’s no surprise, since about two-thirds of the forests in Australia are eucalyptus forests and given the tree’s incredible versatility.

Of course, the eucalyptus’ most cuddly fan is the koala, but indigenous societies, in the past and today, have found many, many uses for this beautiful tree. For one, they invented a technique for using long strips of tree’s bark to make impressive and very strong canoes for navigating the rivers. The wood itself is great for drinking vessels, musical instruments, spear-throwers, shields, and, of course, boomerangs! Aside from this, the leaves, which are famously fragrant, have medicinal and therapeutic properties helping people globally. Their oil has also proven effective as a naturally based insecticide.

Today, you can find species of eucalyptus around the globe in appropriate climates. In California they were planted by the tens of thousands to create massive windbreaks to protect the agricultural sector that has since gone on to feed billions. The beauty and utility of the eucalyptus is timeless but does stand at the risk of increasingly destructive wildfires in Australia, California, and elsewhere.

Drinking vessels and sturdy canoes are just a few of the indigenous inventions that make use of the eucalyptus tree. Sources: Australia National Botanic Gardens.

Sources:

Australia National Botanic Gardens, website: https://anbg.gov.au/index.html

Childhood:

Initiation

Initiation

Though there is a universality in the biological life sequence from child to adult, the significance and ritualization of that biographical transition varies throughout cultures. Some key components, like social assimilation through education, the importance of play as preparation for adult life, and generally a clear ceremonial ‘break’ into adulthood generally appear across cultural landscapes. Here we present two singular slices of childhood in indigenous society that demonstrate both the recognizable universality and contextual uniqueness of each culture’s experience of being a child.

Krahó child playing with a blue area. (Photo: Harald Schultz. In: Schultz. 1962).

Sources:

SCHULTZ, H. Humbu: Indian life in the Brazilian jungle. New York: Macmillan, 1962.

Initiation

Though there is a universality in the biological life sequence from child to adult, the significance and ritualization of that biographical transition varies throughout cultures. Some key components, like social assimilation through education, the importance of play as preparation for adult life, and generally a clear ceremonial ‘break’ into adulthood generally appear across cultural landscapes. Here we present two singular slices of childhood in indigenous society that demonstrate both the recognizable universality and contextual uniqueness of each culture’s experience of being a child.

Krahó child playing with a blue area. (Photo: Harald Schultz. In: Schultz. 1962).

Sources:

SCHULTZ, H. Humbu: Indian life in the Brazilian jungle. New York: Macmillan, 1962.

Sand stories of the Anangu

Sand stories of the Anangu

Storytelling and play acting are common ways for children to “dress rehearse” for the ‘real world’ they imagine later in life. Children often mimic the demeanor and demands of adulthood and role play these projections of their future together in groups. While the Barbie Doll and action figure may perform this function in industrial globalized economies, the children of the APY Lands in South Australia make do with a variety of leaves as the surrogate actors in their ‘sand stories’.

Different sizes and shapes of leaves can fulfill the role of different people ‘types’ (for example yellow leaves are half-Aboriginal characters), and the leaves can be manipulated to act out certain stories (two larger leaves puncturing a small leaf with a stick can represent the punishment of a badly behaved child). Out of sight from the adults and boys, older girls act out stories from the community or relay stories of archetypal animal figures representing specific personality types, while the younger children watch.

This accessible form of play theater reiterates community values, acts as a gossip forum, and allows for creativity and a safe space for challenging community norms and taboos. In that sense, it seems like a very familiar form of social play that helps children form their adult identities while comparing ideas about their world and themselves with their peers.

Child depicting in the sand the floor plan and furniture of a house. (Eickelkamp, 2008).

Sources:

EICKELKAMP, U. (Re)presenting Experience: A Comparison of Australian Aboriginal Children’s Sand Play in Two Settings. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 5(1): 23–50, 2008.

TJITAYI, K.; LEWIS, S. ‘Envisioning Lives at Ernabella’, In: Growing Up in Central Australia: New Anthropological Studies of Aboriginal Childhood and Adolescence, Ute, E.(ed.), Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2011.

Sand stories of the Anangu

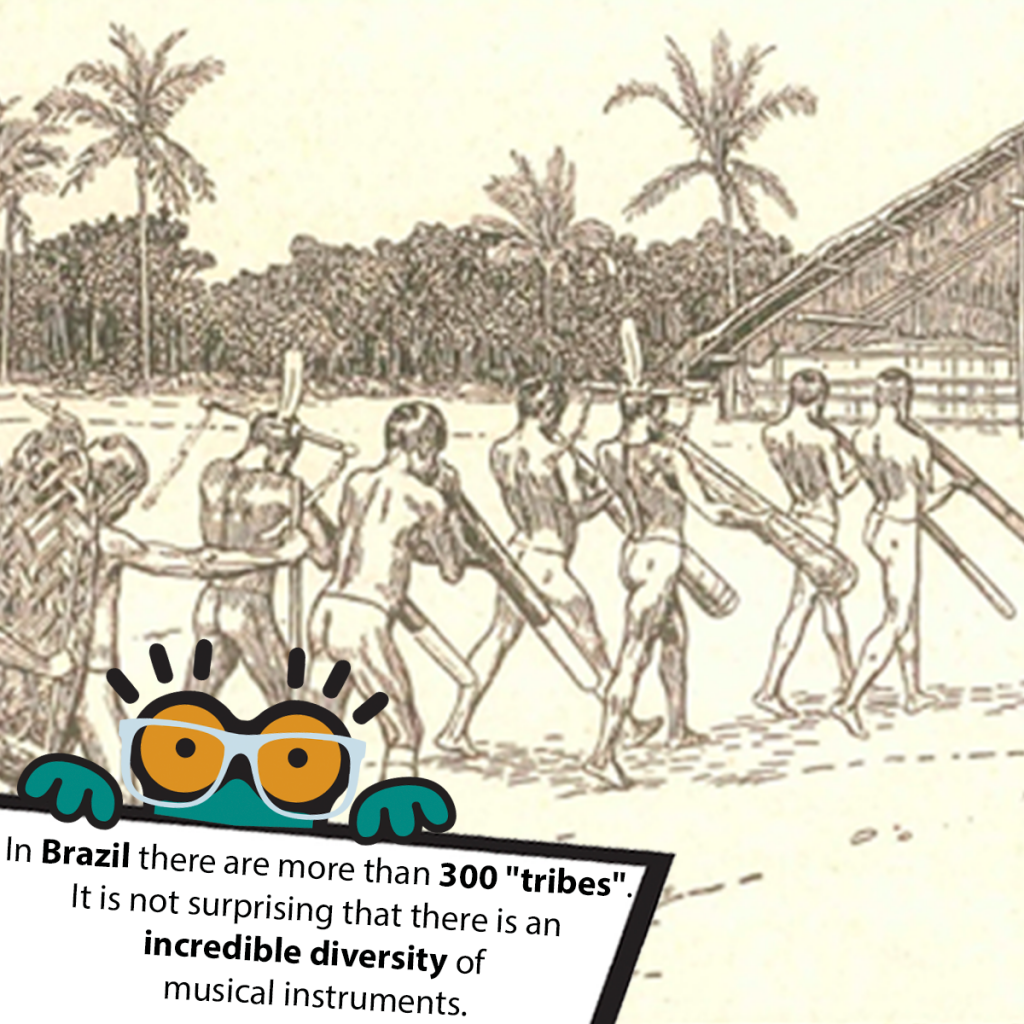

Storytelling and play acting are common ways for children to “dress rehearse” for the ‘real world’ they imagine later in life. Children often mimic the demeanor and demands of adulthood and role play these projections of their future together in groups. While the Barbie Doll and action figure may perform this function in industrial globalized economies, the children of the APY Lands in South Australia make do with a variety of leaves as the surrogate actors in their ‘sand stories’.